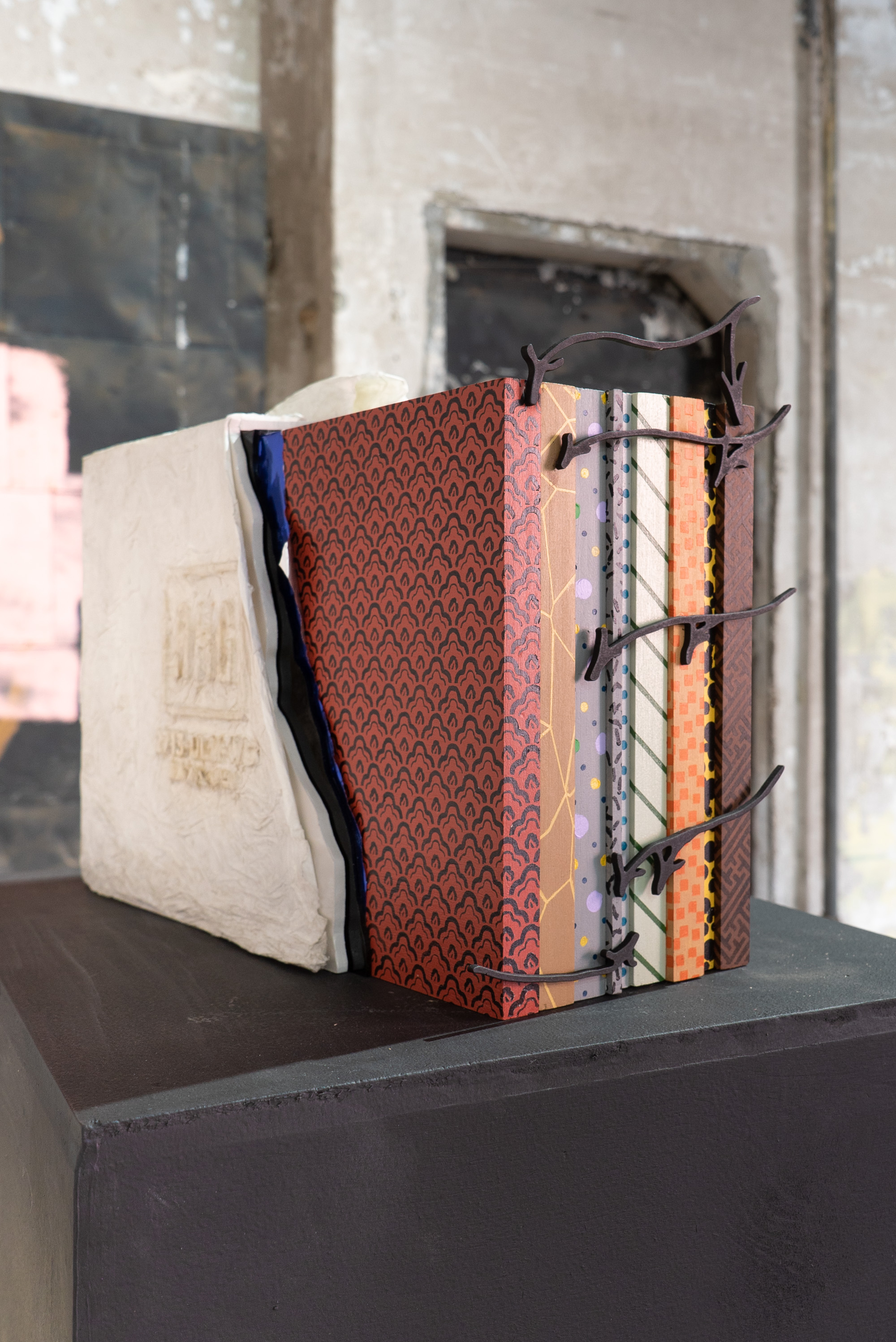

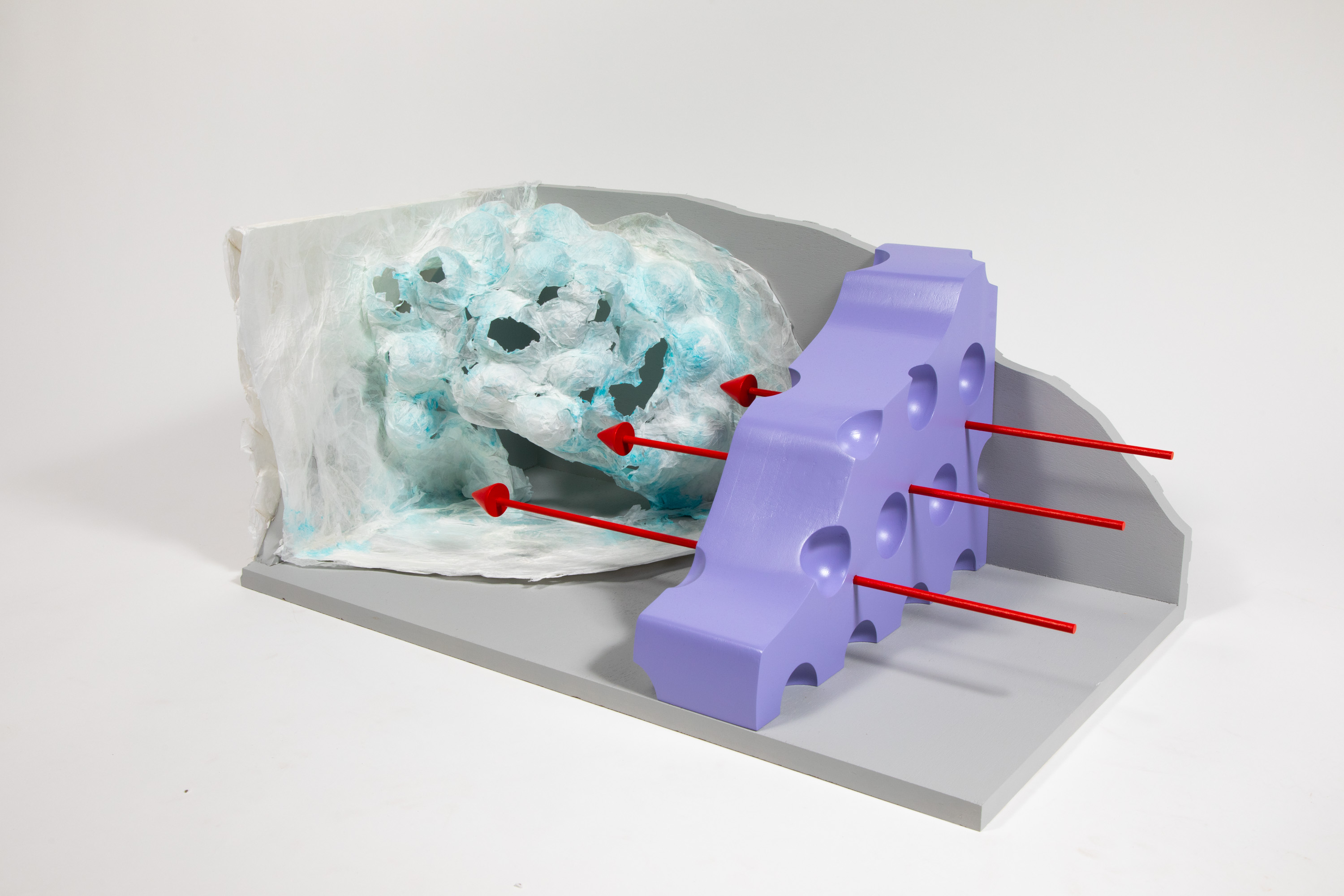

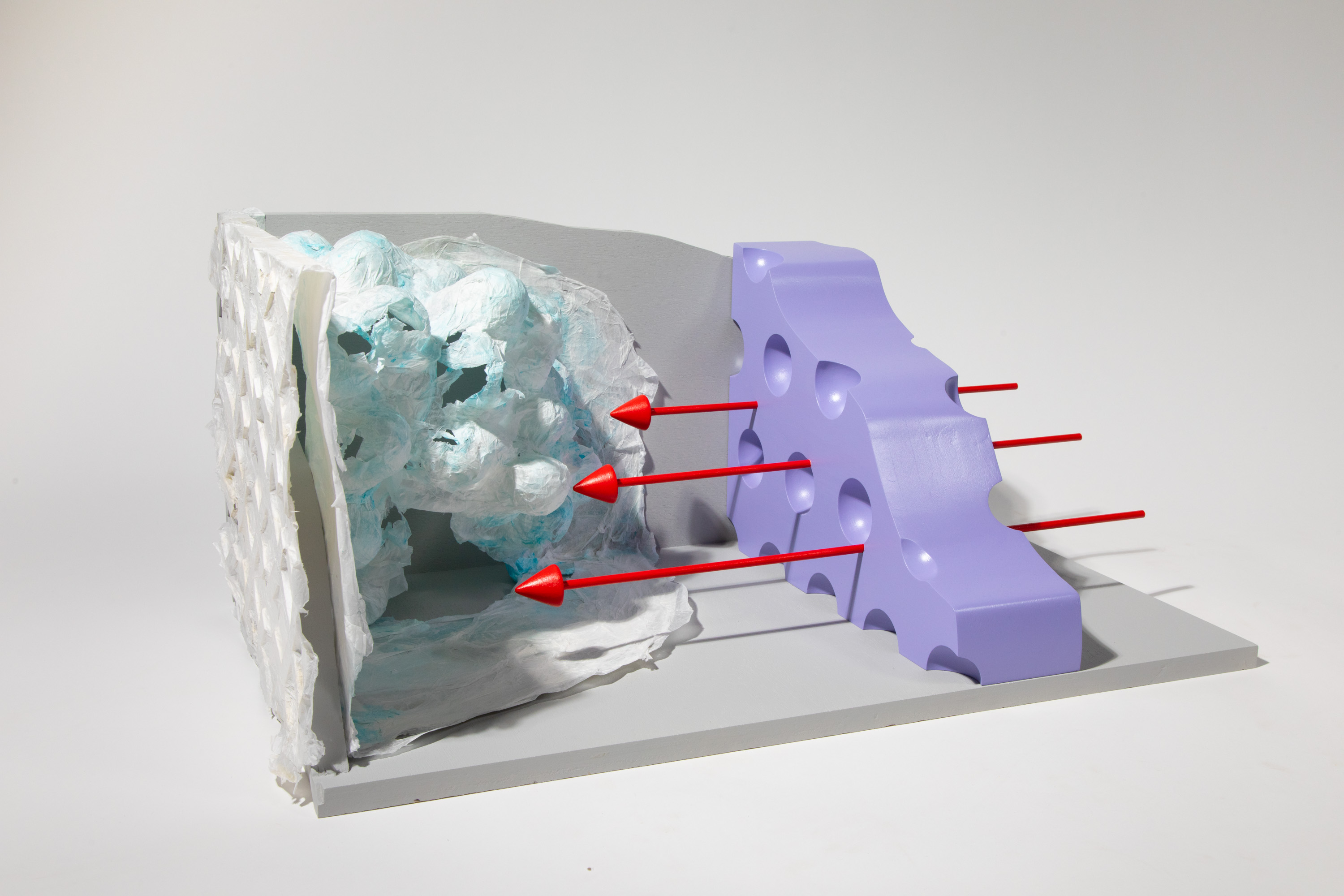

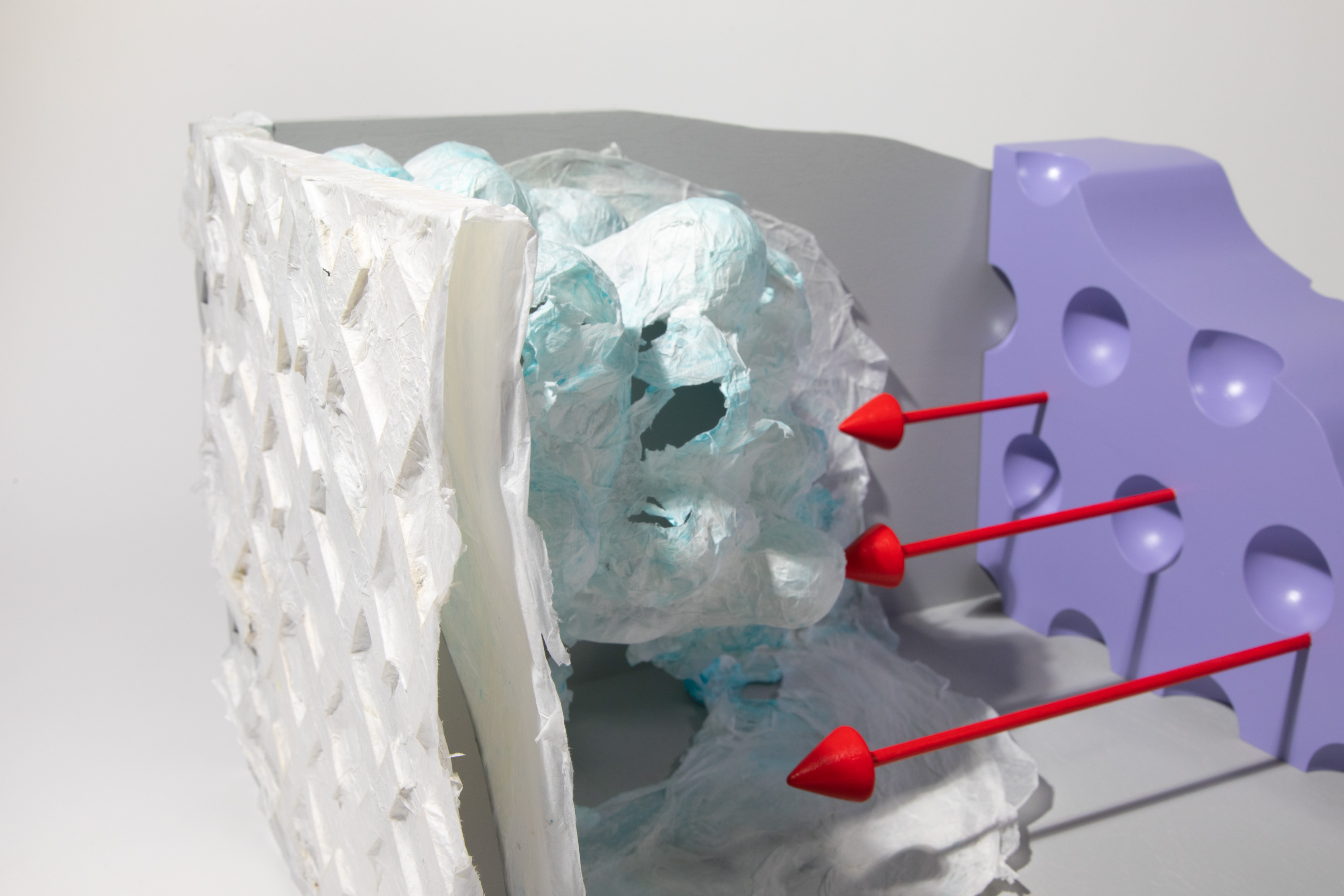

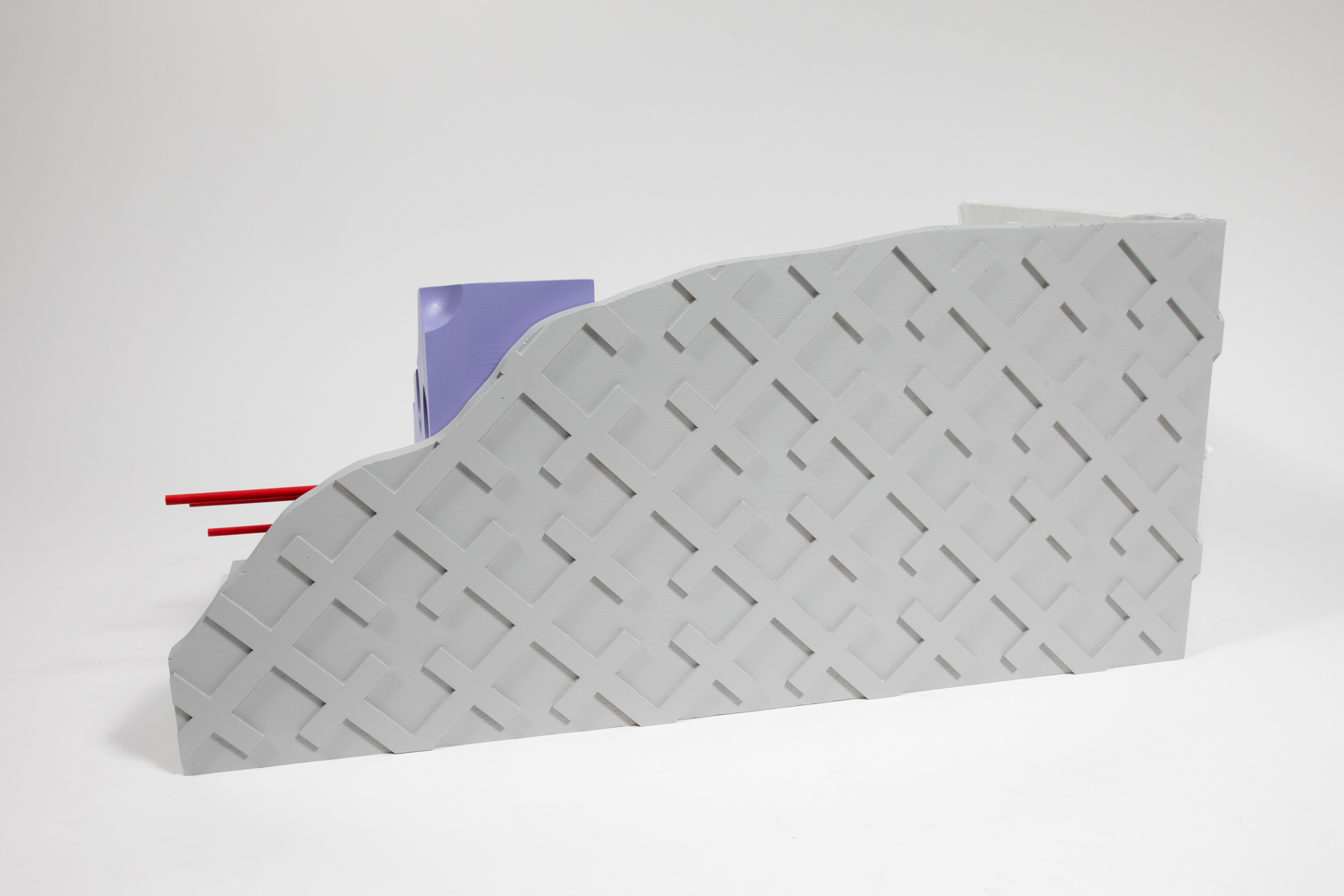

Collector

I was reading a book on the history of batteries in which the author used the terms “evolution” and “adaptation” purposefully to relate the development of battery technology to biological change. Simultaneously, an enormous proportion of the current “good news” on climate change is about battery advances. The works in this series are inspired by the little ecosystems depicted in battery diagrams. I am deconstructing, blending, and reconfiguring the them, imagining new relationships and entities and thinking about our own interconnectedness.

Collector

2023

Plywood, MDF, acrylic, tissue paper, polyethylene

12 x 16 x 8 in.

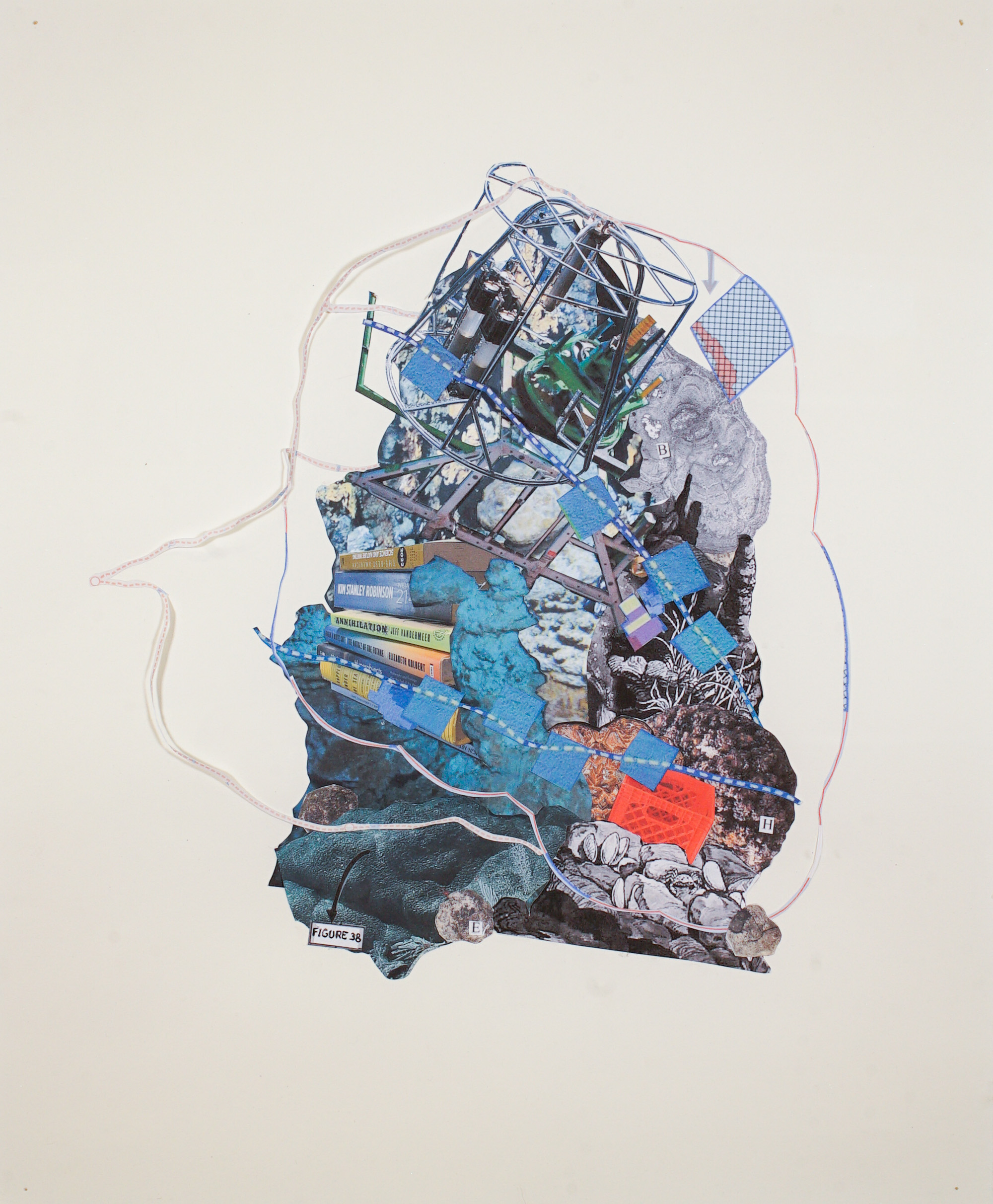

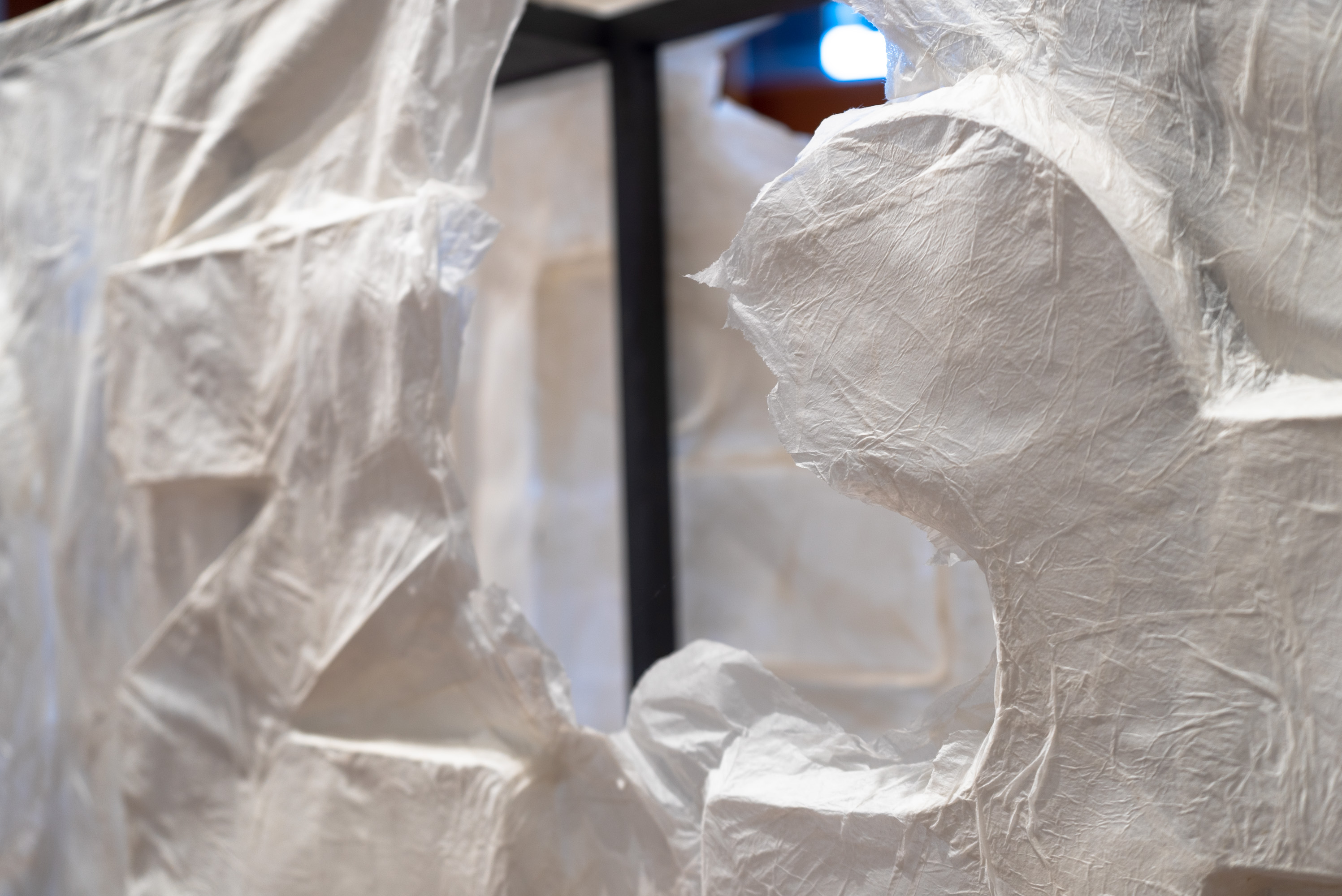

Waiting in the Deep, No. 1

Waiting in the Deep, No. 1 is an exploration of the complicated and entangled issues around deep sea mining. Metals such as nickel, manganese, and cobalt are crucial to battery technology, and thus to climate action as a whole. But the ocean floor is a vibrant and ancient ecosystem that we know very little about. Some organisms living near hydrothermal vents may be almost as old as the Earth itself. What we already know about these organisms is that they are profoundly entangled with, connected to, and contingent upon their environment—as are we.

An alliance of 24 countries oppose deep sea mining, but Norway has recently approved it. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is supposed to finalize regulations by 2025.

Waiting in the Deep, No. 1

2023

Molded tissue paper

39 x 50 x 28 in.

SKETCHES

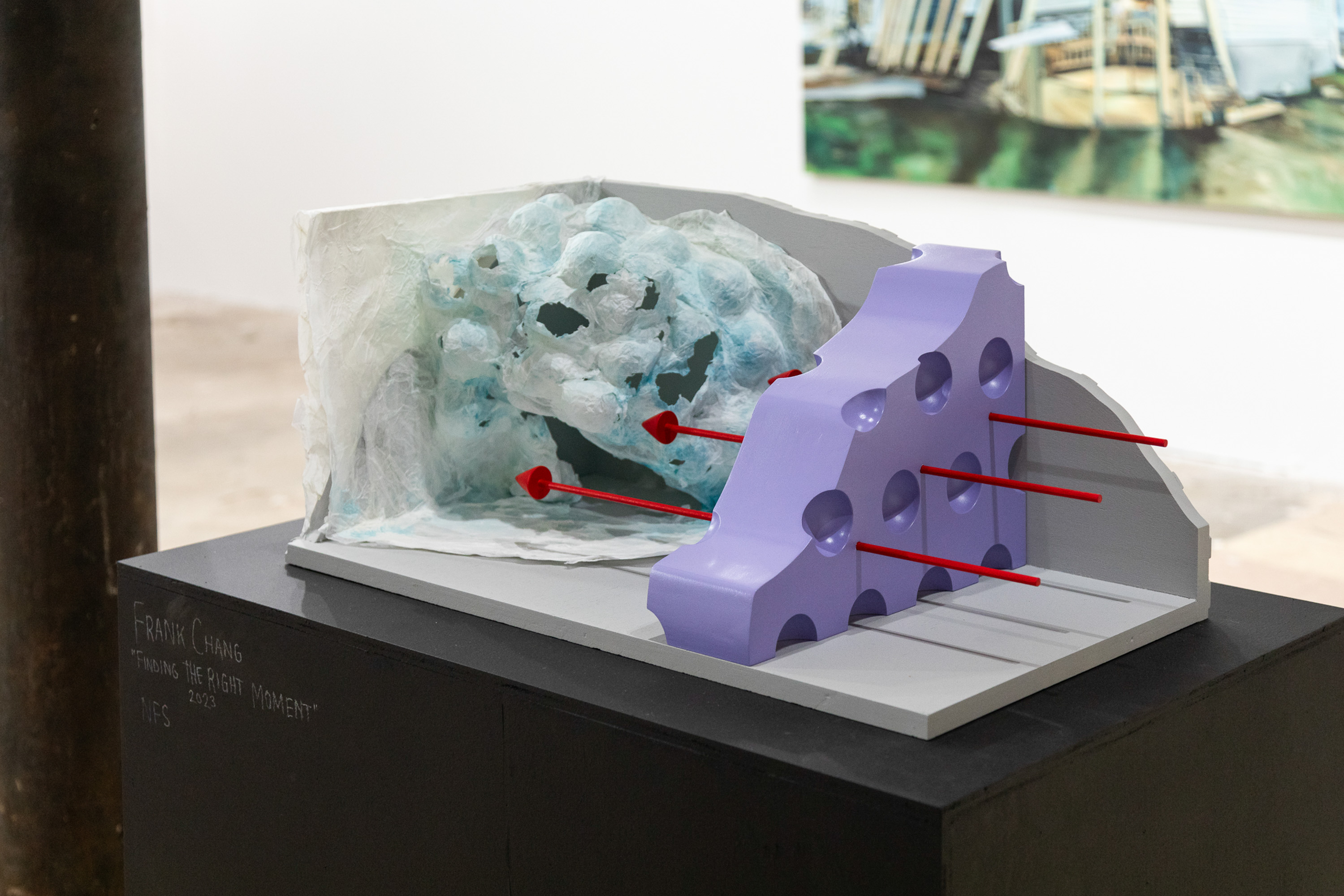

Finding the Right Moment

I was reading a book on the history of batteries in which the author used the terms “evolution” and “adaptation” purposefully to relate the development of battery technology to biological change. Simultaneously, an enormous proportion of the current “good news” on climate change is about battery advances. The works in this series are inspired by the little ecosystems depicted in battery diagrams. I am deconstructing, blending, and reconfiguring the them, imagining new relationships and entities and thinking about our own interconnectedness.

Finding the Right Moment

2023

Plywood, pine, MDF, spray paint, tissue paper

28 x 16 x 13 in.

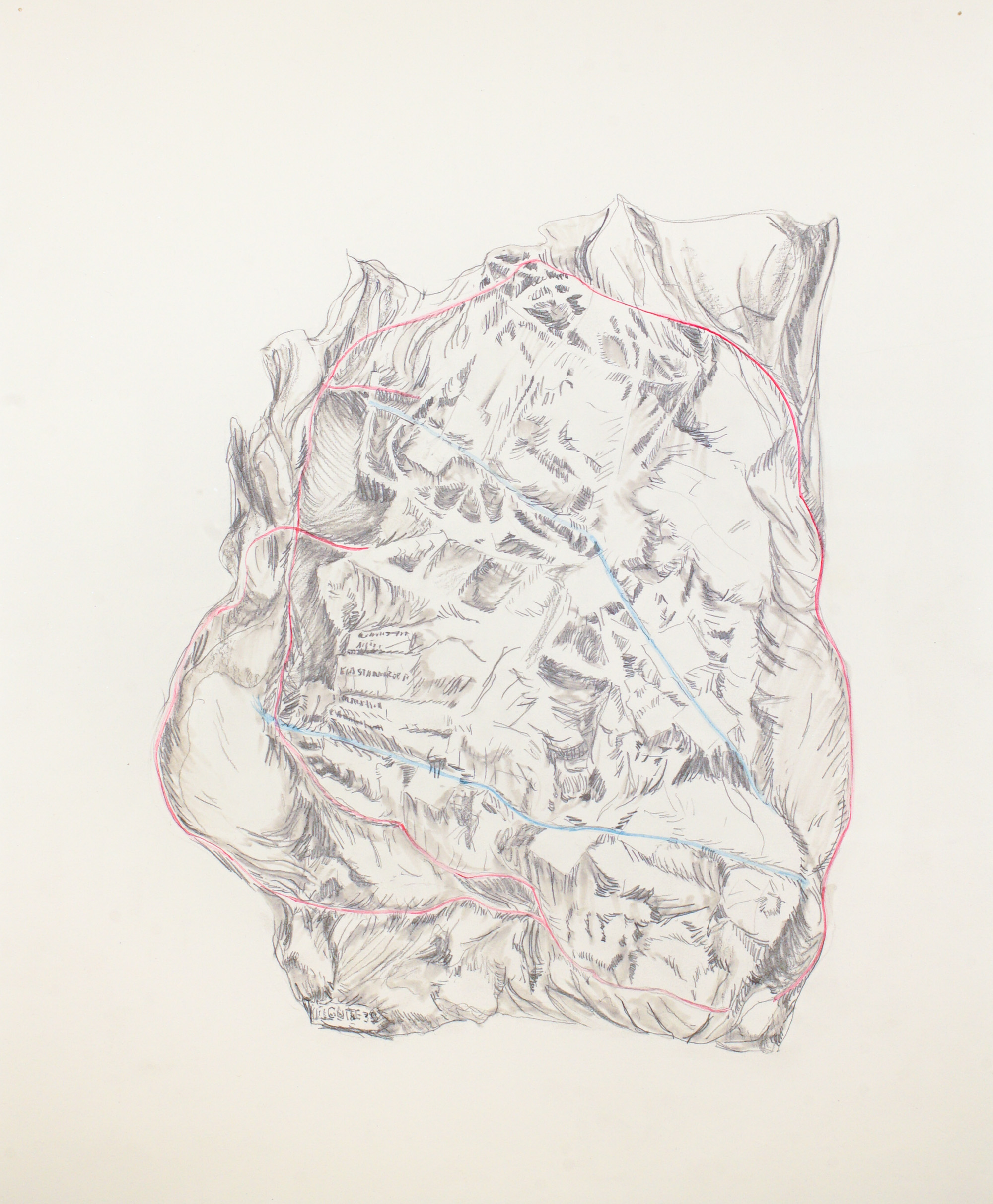

The Start of a Wave

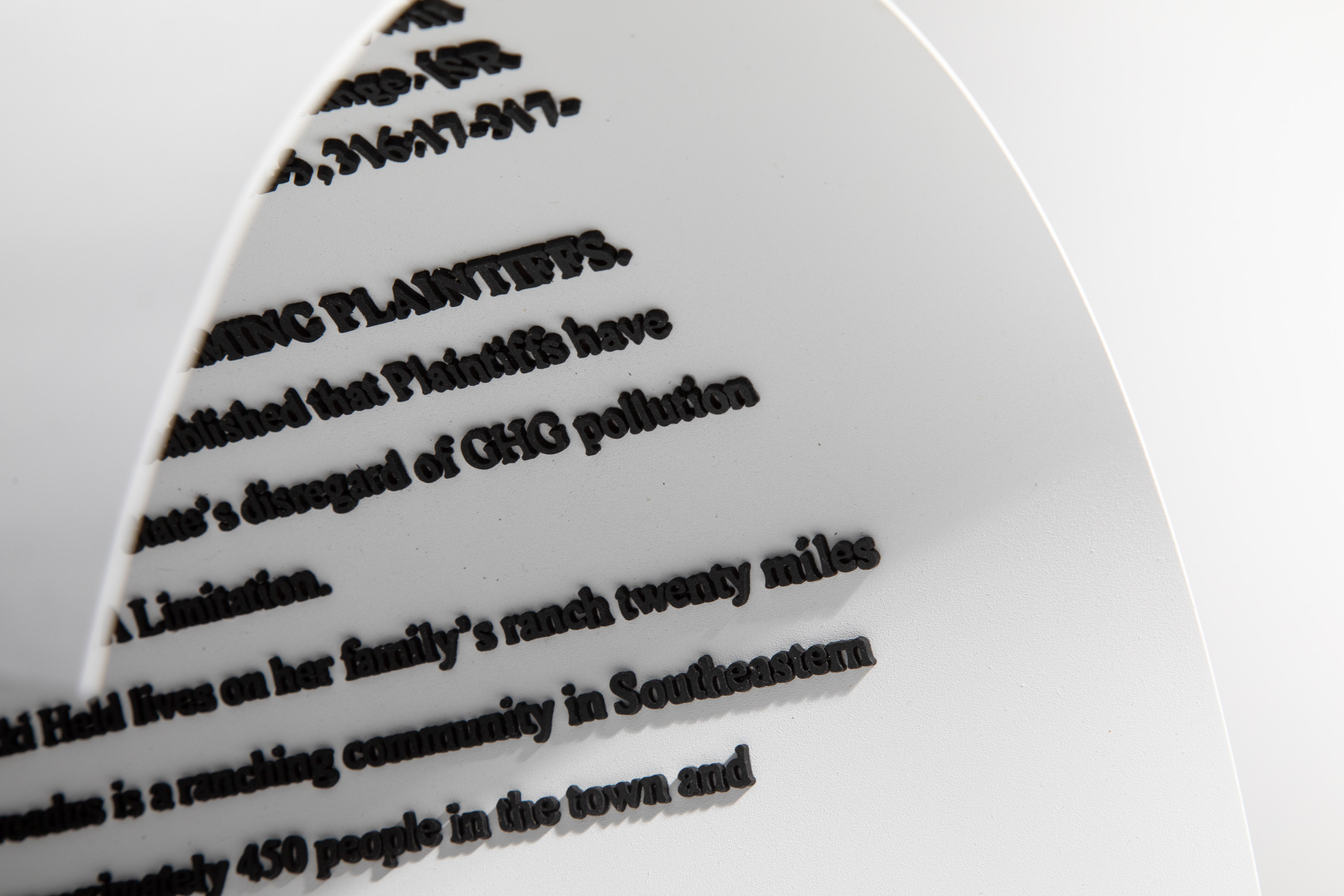

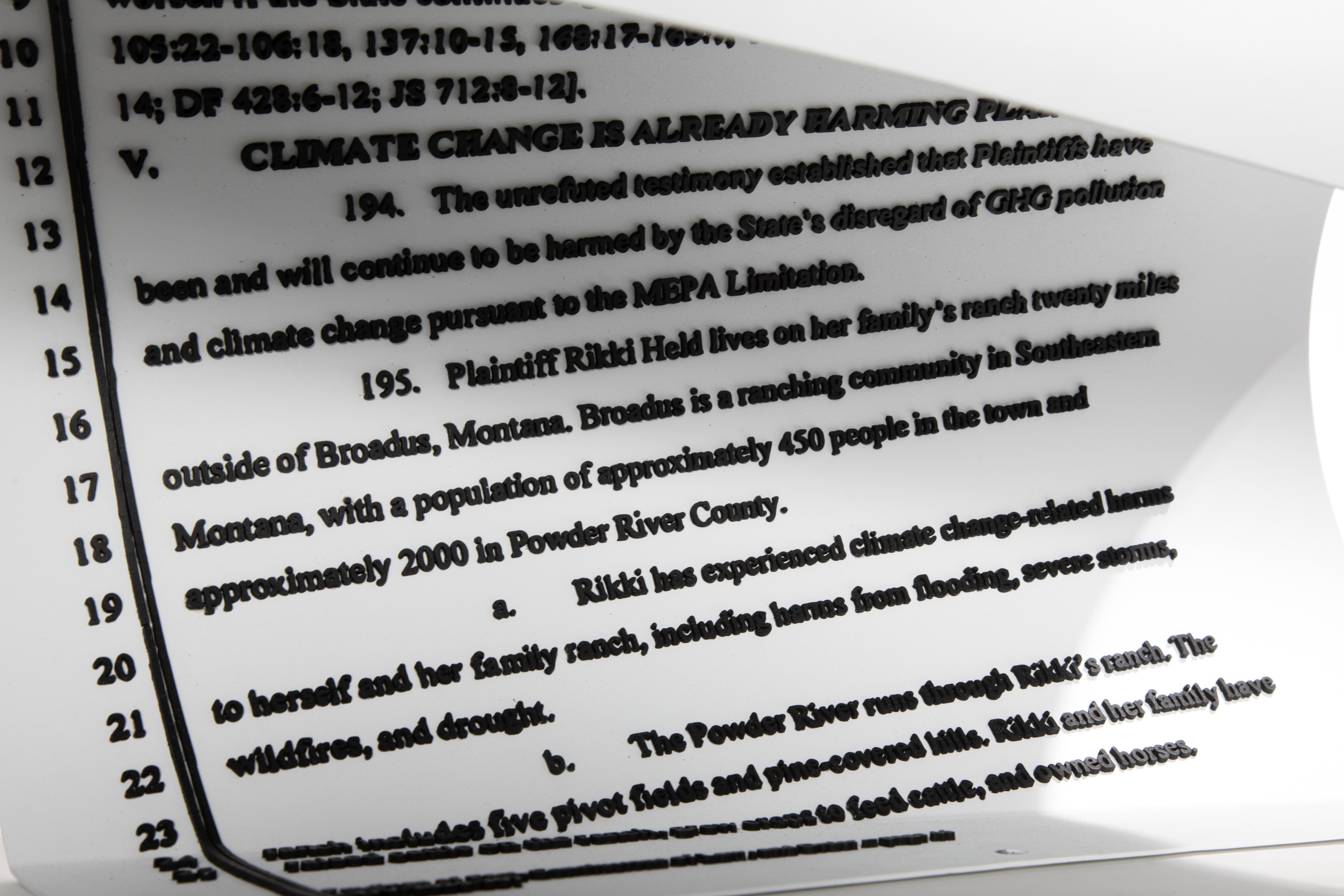

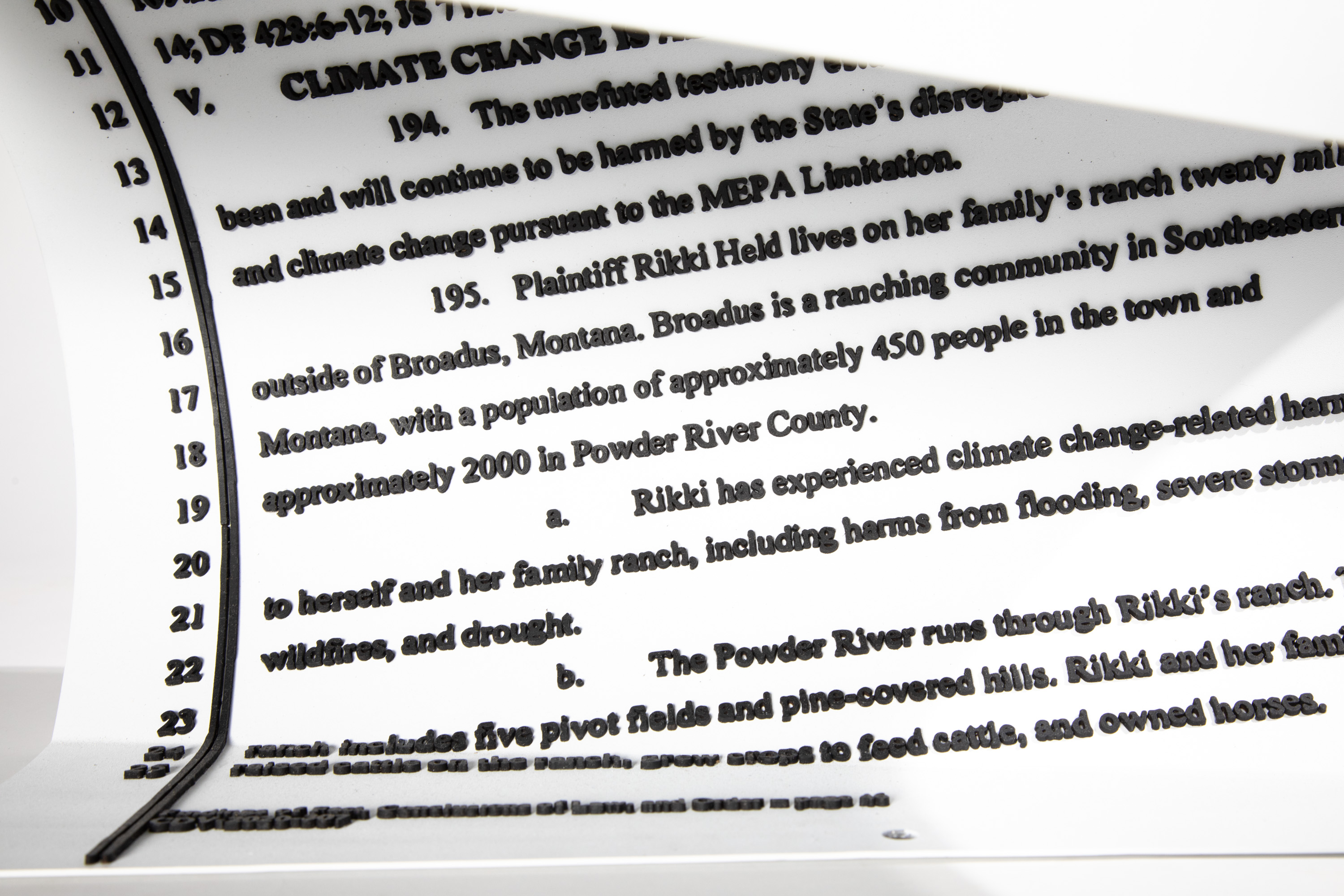

A sculpture or proposal for a monument based on a page from the Montana climate case ruling (Held v. Montana). The wave refers to the upcoming wave of global lawsuits framing climate change as a violation of fundamental human rights.

The Start of a Wave

2023

Steel, laser cut modeling board, paint

20 x 10 x 12 in.

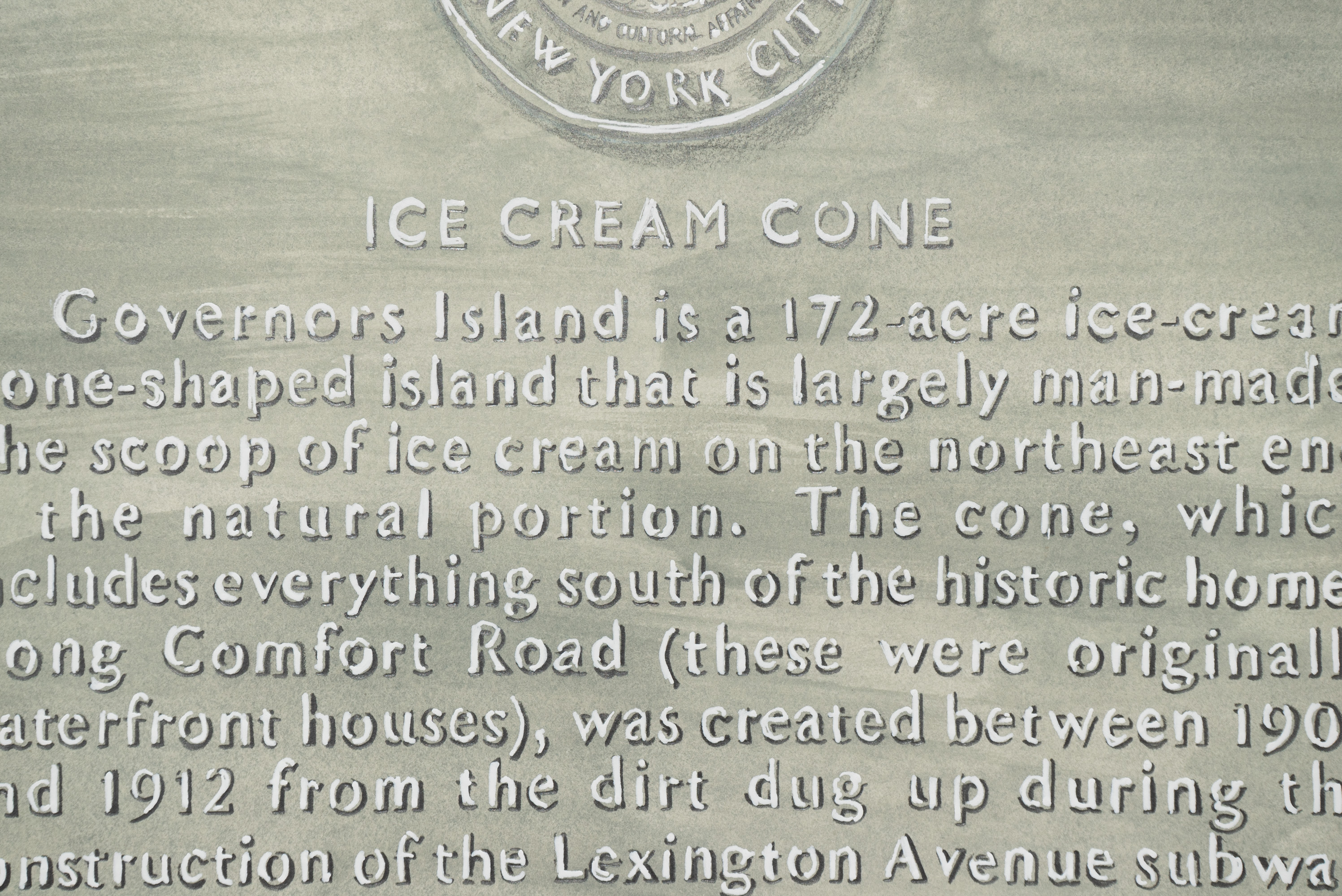

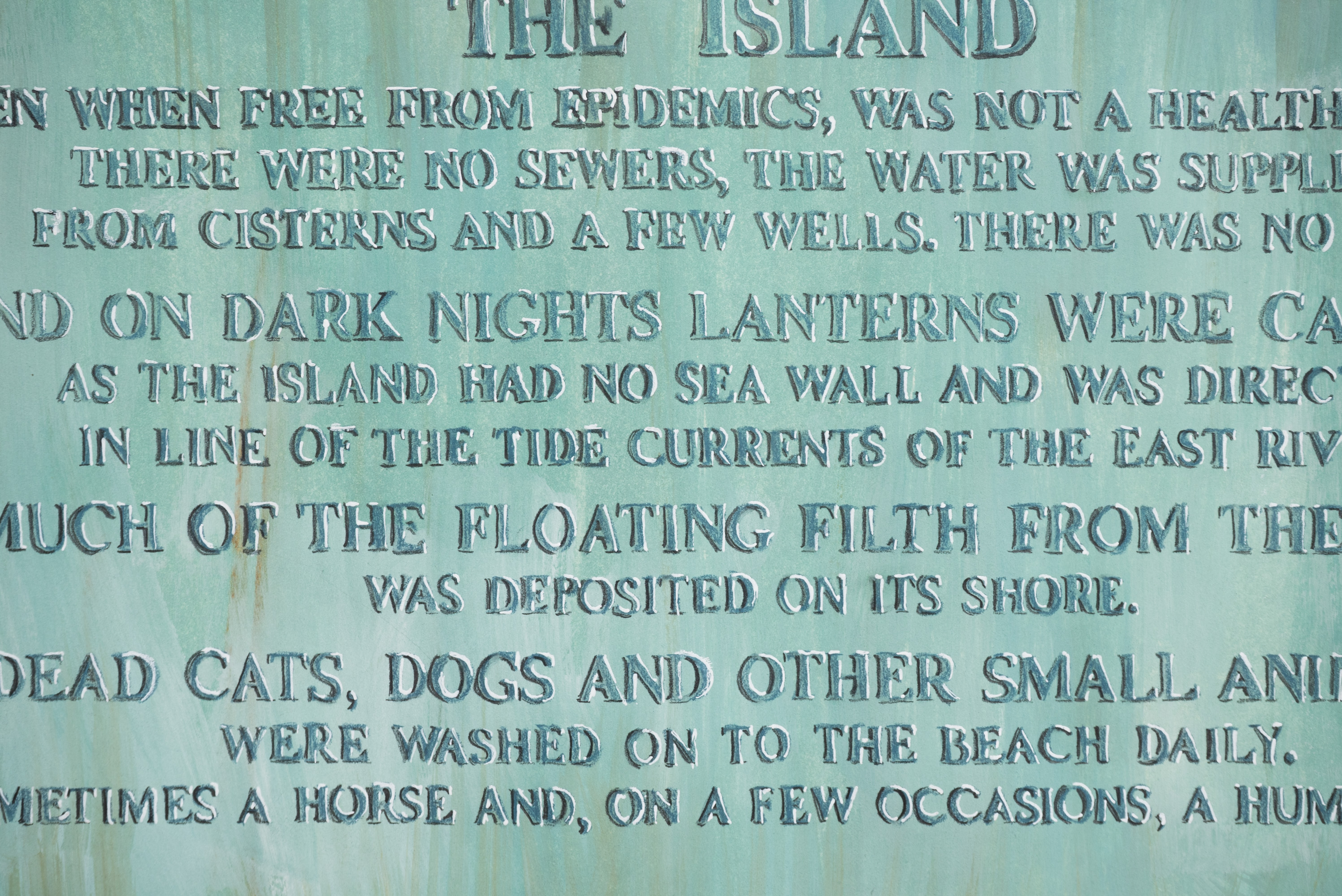

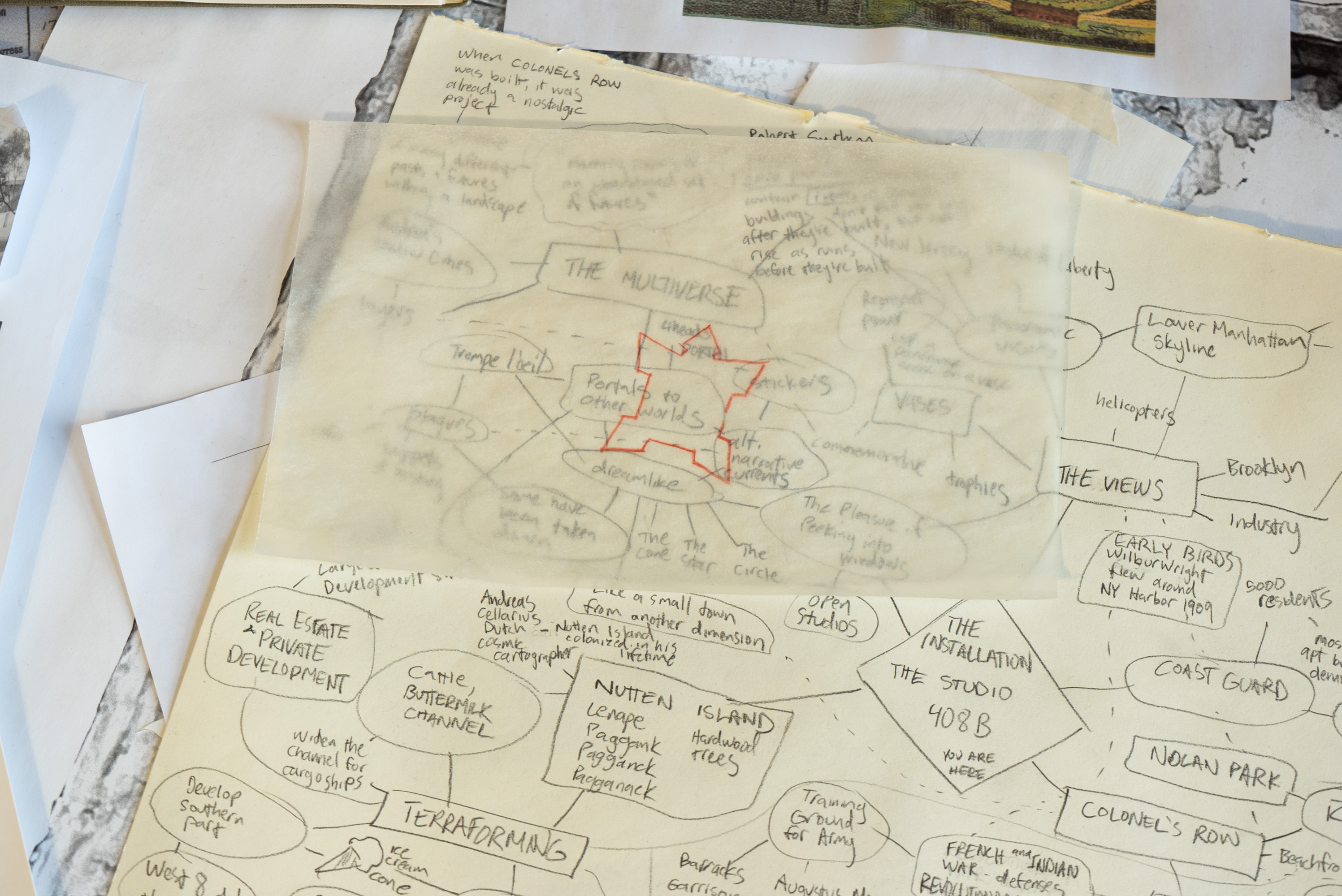

Governors Island Residency

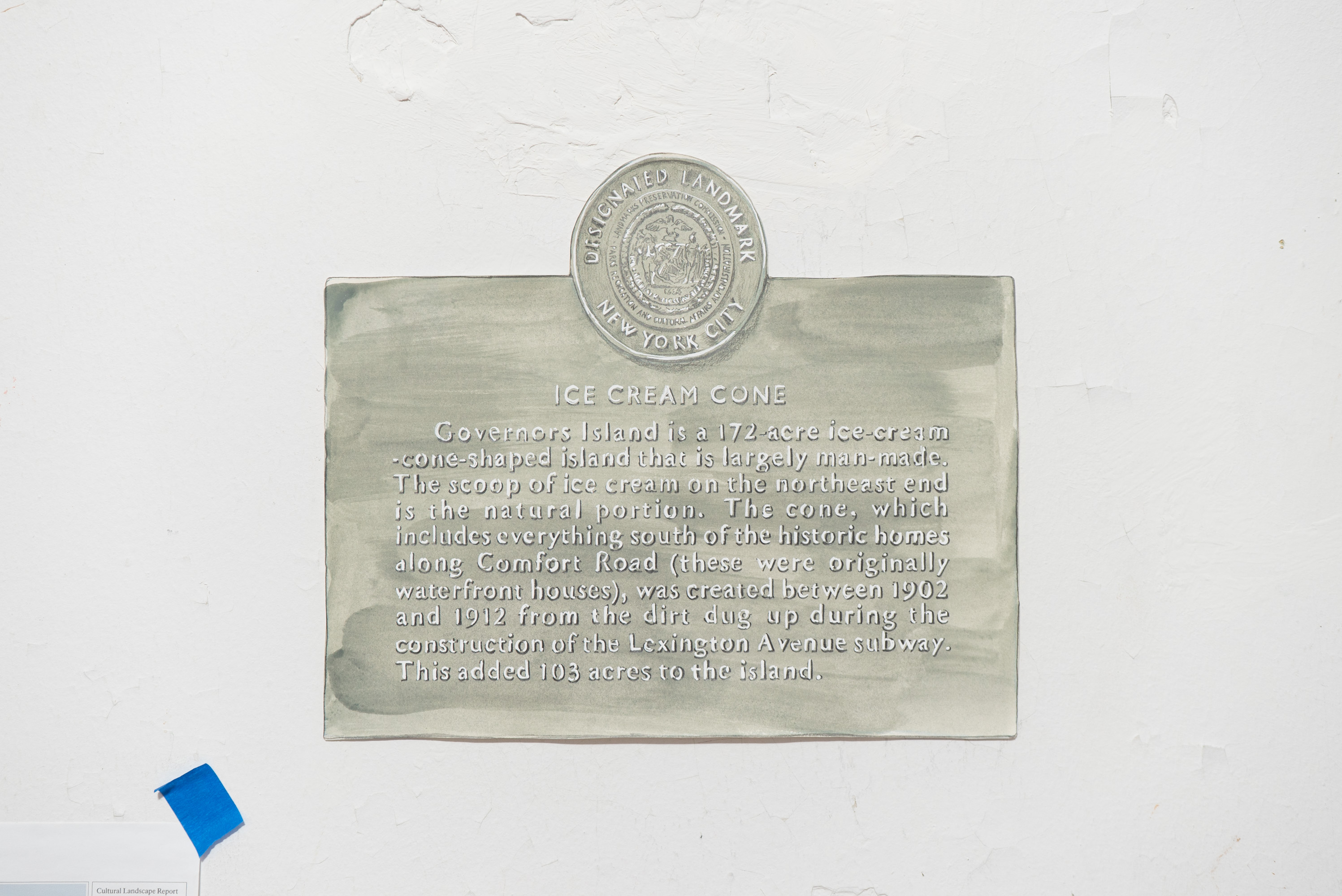

At Rest and In Motion was a collaborative residency project with Andrea Kastner investigating the fascinating history of Governors Island.

The island’s stunning views—of NY Harbor, lower Manhattan, and the Statue of Liberty—were the starting point from which we explored its history and possible futures. Surveying and looking became a through line for our project, and we followed this trail through the island’s history—from cannon defense lines, to beachfront officers’ homes, the industrial sublime, and even ghost sightings.

At Rest and In Motion (in collaboration with Andrea Kastner)

2022

Mixed media installation in Building 408B, Colonels’ Row, Governors Island

Dimensions variable

INSANITY MONOTONY

INSANITY MONOTONY

2021

Molded paper, wood, paint

Two sections, 76 x 36 x 9 in. and 38 x 21 x 9 in.

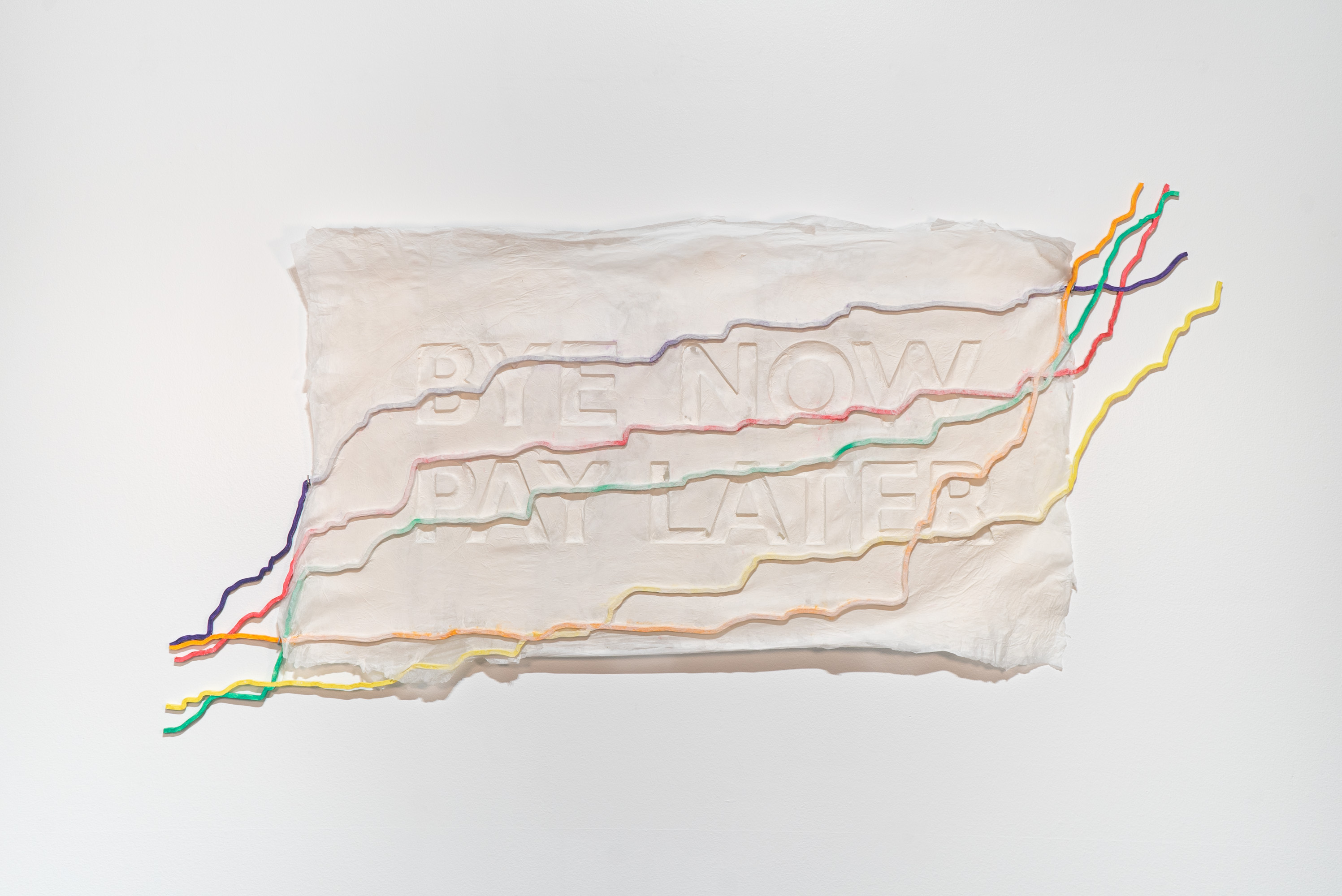

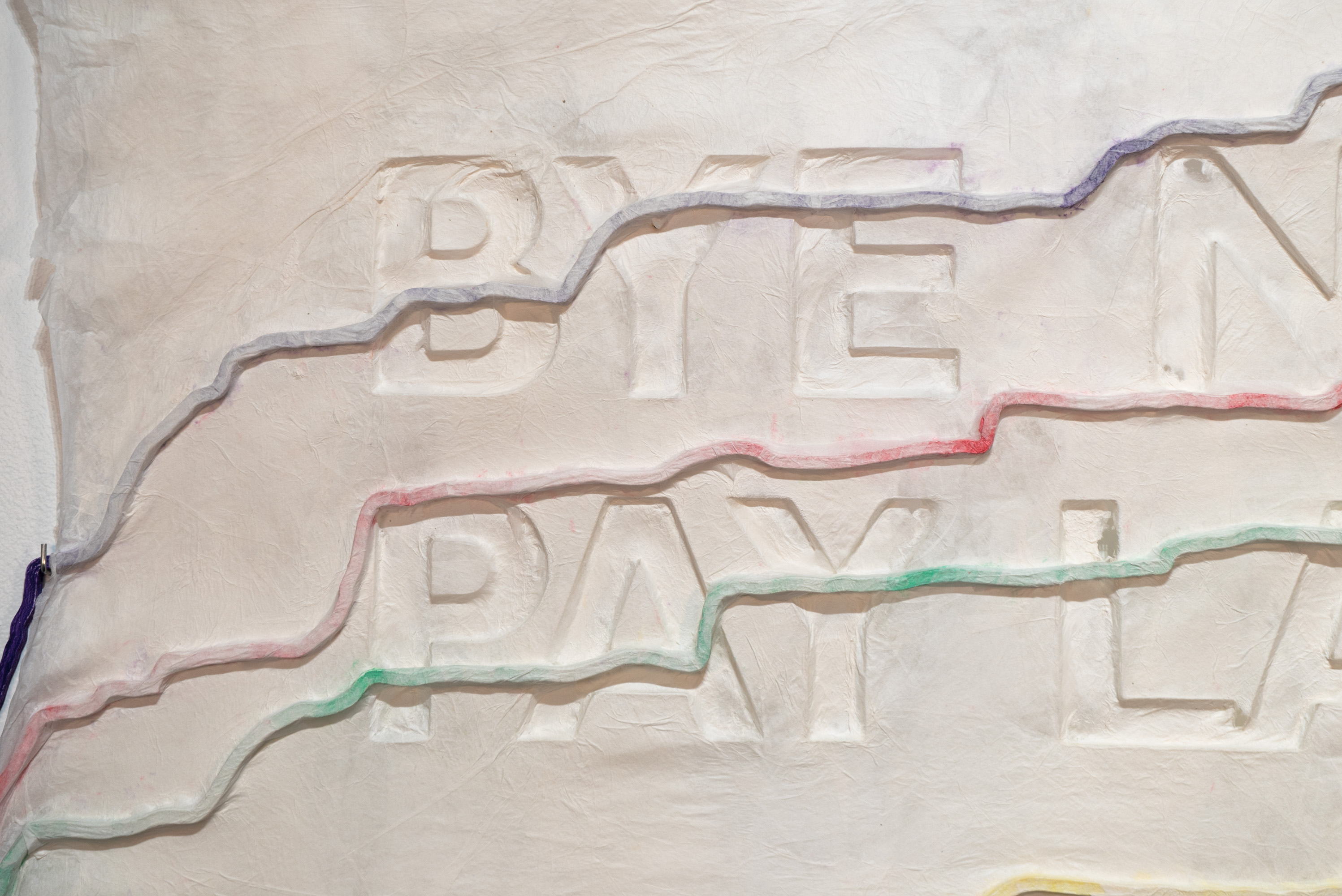

Bye Now

Pay Later

2021

Molded paper, wood, paint

47 1/2 x 24 in.

Rising

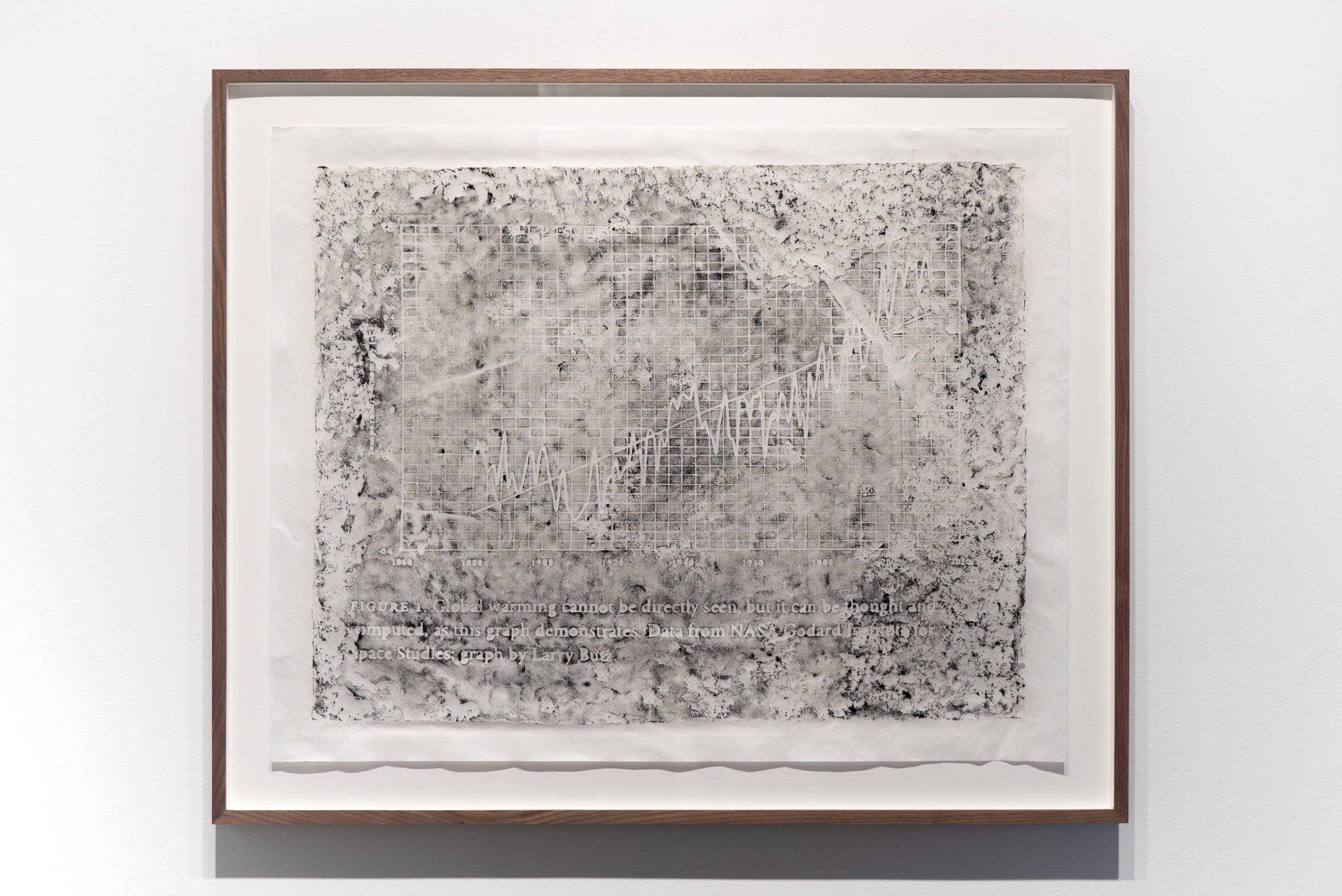

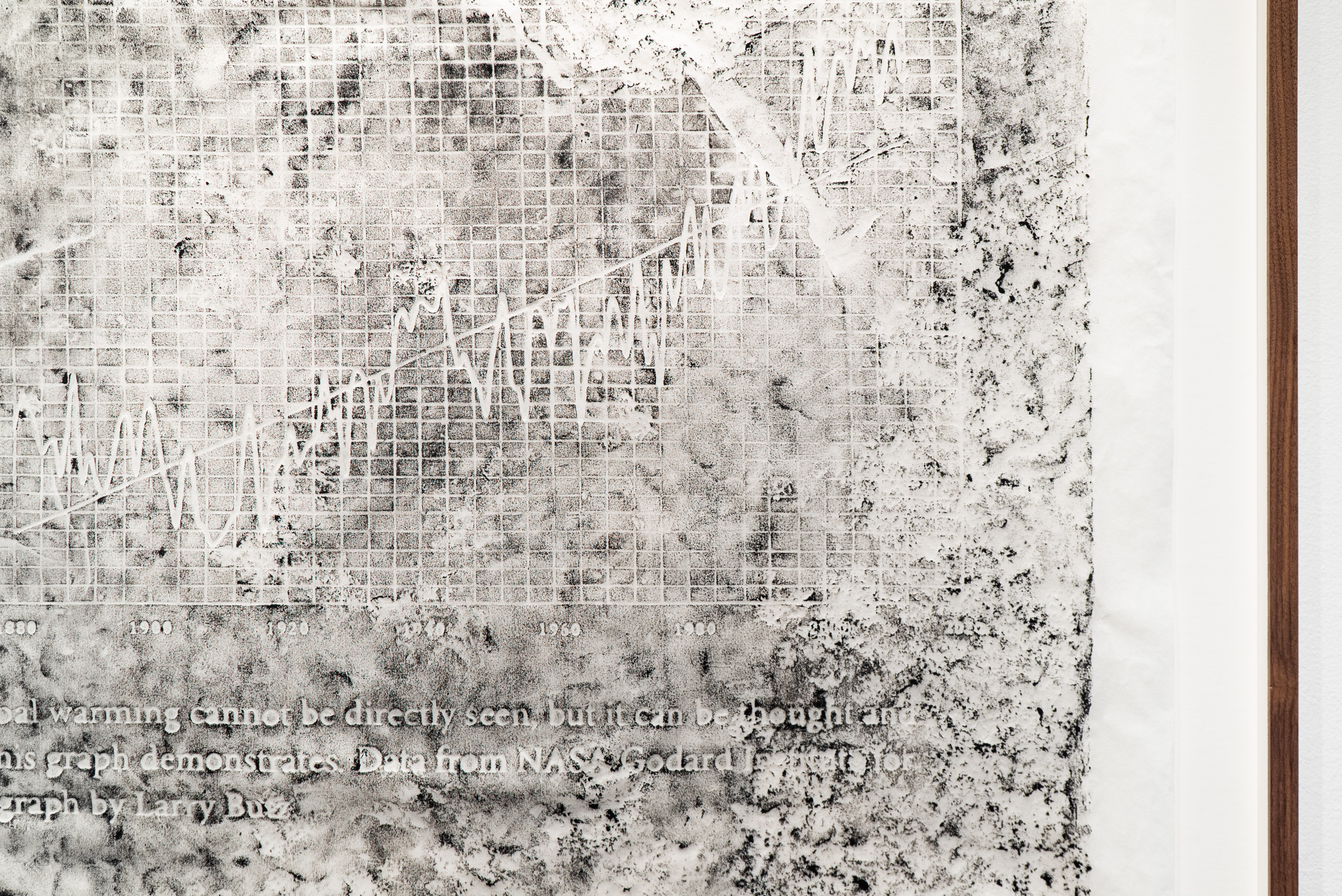

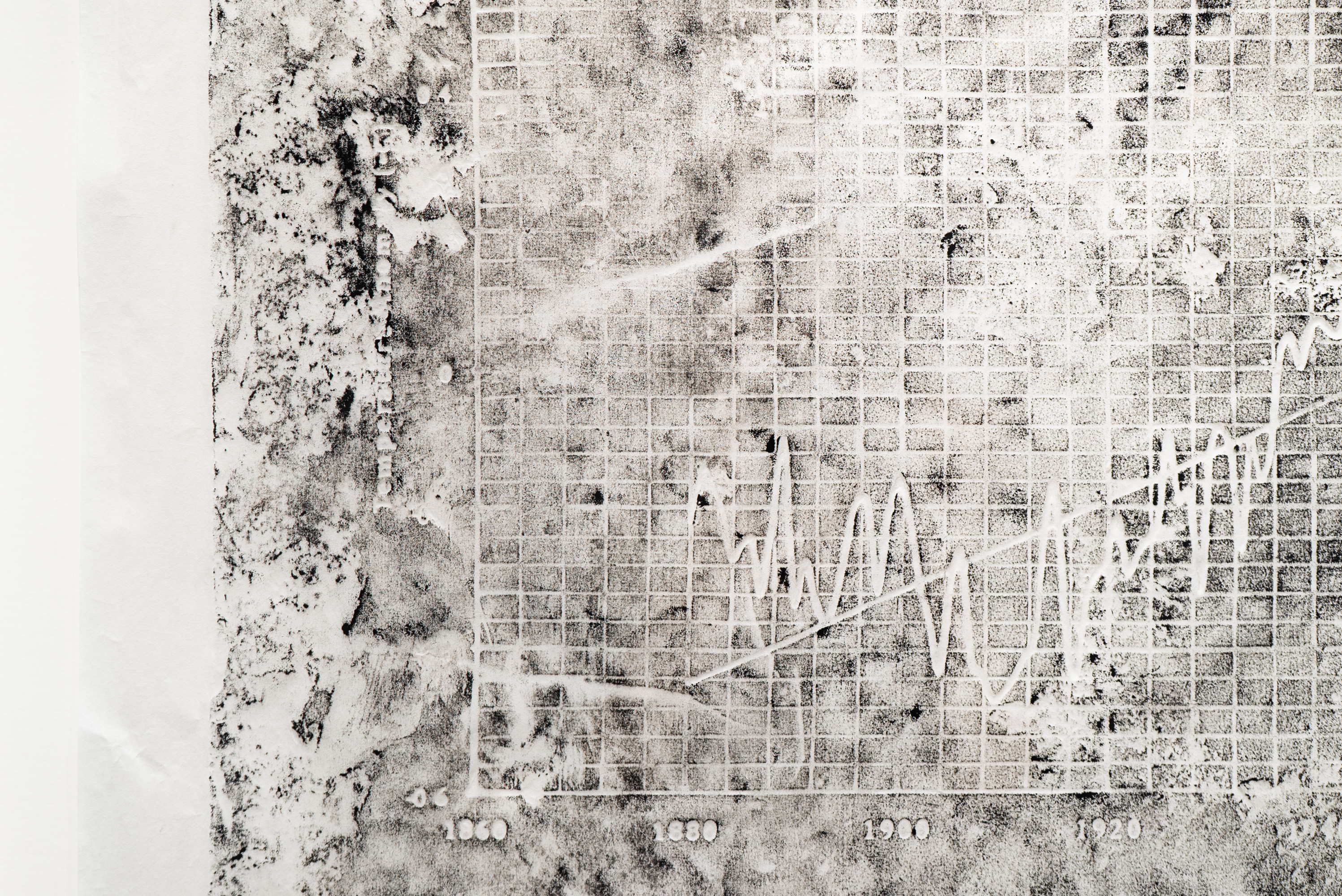

This is a rubbing of the Global Surface Temperature Index, which can be thought of as the planet’s vital signs for global warming. When global warming targets are talked about, such as limiting temperature rise to 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius, this is the data that is referenced.

The warmest seven years on record have all been since 2015, and the warmest 20 years since 2000.

Rising

2021

Rubbing on xuan paper

34 x 27 in.

1880 -0.16 -0.09 1881 -0.08 -0.13 1882 -0.11 -0.16 1883 -0.17 -0.20 1884 -0.28 -0.24 1885 -0.33 -0.26 1886 -0.31 -0.27 1887 -0.36 -0.27 1888 -0.17 -0.26 1889 -0.10 -0.25 1890 -0.35 -0.25 1891 -0.22 -0.25 1892 -0.27 -0.26 1893 -0.31 -0.26 1894 -0.30 -0.23 1895 -0.22 -0.22 1896 -0.11 -0.20 1897 -0.10 -0.18 1898 -0.27 -0.16 1899 -0.17 -0.17 1900 -0.08 -0.20 1901 -0.15 -0.23 1902 -0.28 -0.26 1903 -0.37 -0.28 1904 -0.46 -0.31 1905 -0.26 -0.34 1906 -0.22 -0.36 1907 -0.38 -0.37 1908 -0.42 -0.39 1909 -0.48 -0.40 1910 -0.43 -0.41 1911 -0.43 -0.38 1912 -0.35 -0.34 1913 -0.34 -0.32 1914 -0.15 -0.30 1915 -0.13 -0.30 1916 -0.35 -0.29 1917 -0.46 -0.29 1918 -0.29 -0.29 1919 -0.27 -0.29 1920 -0.27 -0.27 1921 -0.19 -0.26 1922 -0.28 -0.25 1923 -0.26 -0.24 1924 -0.27 -0.23 1925 -0.22 -0.22 1926 -0.10 -0.21 1927 -0.21 -0.21 1928 -0.20 -0.19 1929 -0.36 -0.19 1930 -0.15 -0.19 1931 -0.09 -0.19 1932 -0.16 -0.18 1933 -0.29 -0.17 1934 -0.12 -0.16 1935 -0.20 -0.14 1936 -0.15 -0.11 1937 -0.03 -0.06 1938 0.00 -0.01 1939 -0.02 0.03 1940 0.13 0.06 1941 0.19 0.09 1942 0.07 0.11 1943 0.09 0.10 1944 0.20 0.07 1945 0.09 0.04 1946 -0.07 0.00 1947 -0.03 -0.04 1948 -0.11 -0.07 1949 -0.11 -0.08 1950 -0.18 -0.08 1951 -0.07 -0.07 1952 0.01 -0.07 1953 0.08 -0.07 1954 -0.13 -0.07 1955 -0.14 -0.06 1956 -0.19 -0.05 1957 0.05 -0.04 1958 0.06 -0.01 1959 0.03 0.01 1960 -0.03 0.03 1961 0.06 0.01 1962 0.03 -0.01 1963 0.05 -0.03 1964 -0.20 -0.04 1965 -0.11 -0.05 1966 -0.06 -0.06 1967 -0.02 -0.05 1968 -0.08 -0.03 1969 0.05 -0.02 1970 0.03 -0.00 1971 -0.08 0.00 1972 0.01 0.00 1973 0.16 -0.00 1974 -0.07 0.01 1975 -0.01 0.02 1976 -0.10 0.04 1977 0.18 0.08 1978 0.07 0.12 1979 0.17 0.17 1980 0.26 0.20 1981 0.32 0.21 1982 0.14 0.22 1983 0.31 0.21 1984 0.16 0.21 1985 0.12 0.22 1986 0.18 0.24 1987 0.32 0.27 1988 0.39 0.31 1989 0.27 0.33 1990 0.45 0.33 1991 0.41 0.33 1992 0.22 0.33 1993 0.23 0.33 1994 0.32 0.34 1995 0.45 0.37 1996 0.33 0.40 1997 0.46 0.42 1998 0.61 0.44 1999 0.38 0.47 2000 0.39 0.50 2001 0.53 0.52 2002 0.63 0.55 2003 0.62 0.58 2004 0.53 0.61 2005 0.68 0.62 2006 0.63 0.62 2007 0.66 0.63 2008 0.54 0.64 2009 0.65 0.64 2010 0.72 0.64 2011 0.61 0.66 2012 0.64 0.69 2013 0.67 0.74 2014 0.74 0.78 2015 0.90 0.83 2016 1.02 0.87 2017 0.92 0.91 2018 0.85 0.92 2019 0.98 0.93 2020 1.02 0.94 2021 0.85 0.94

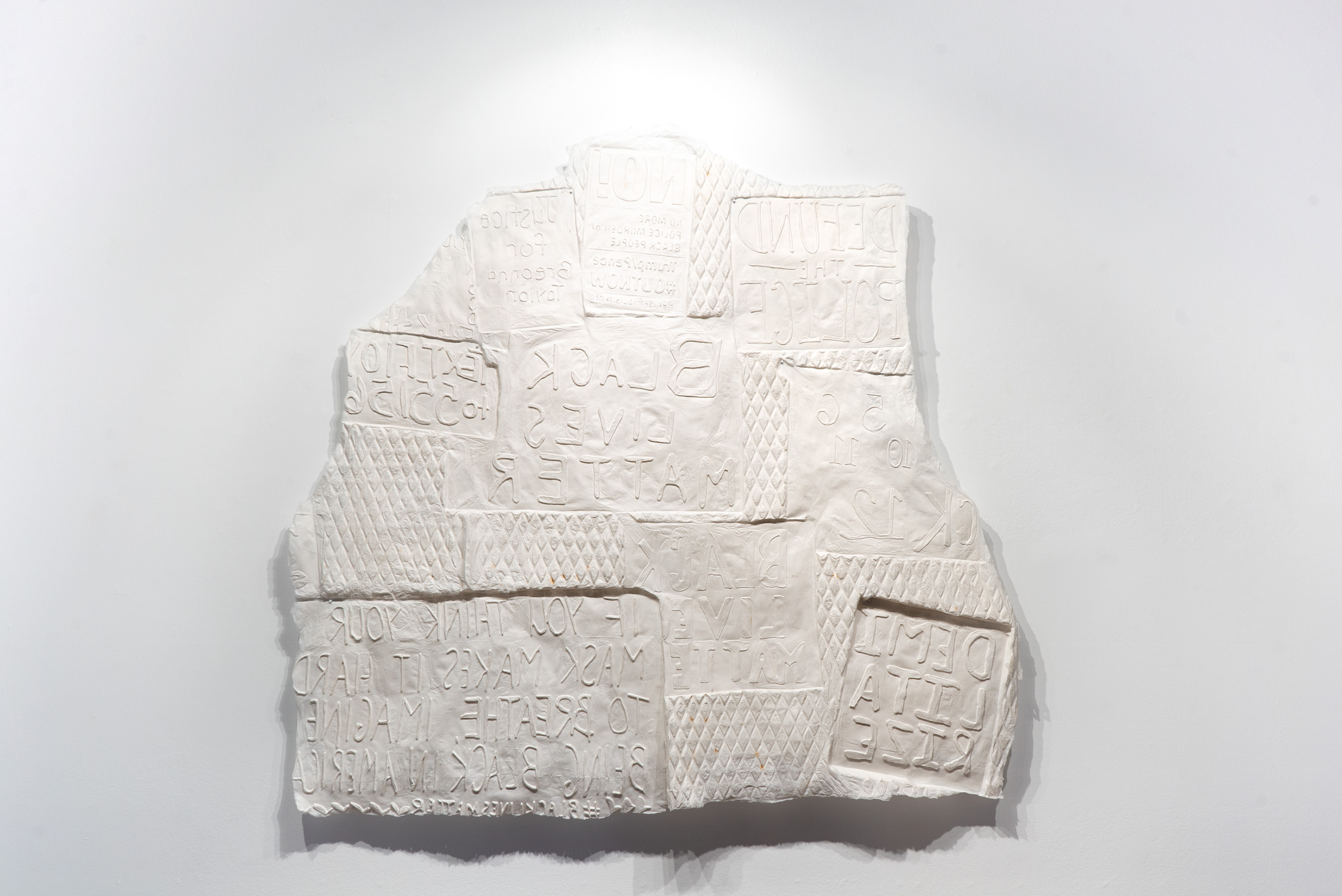

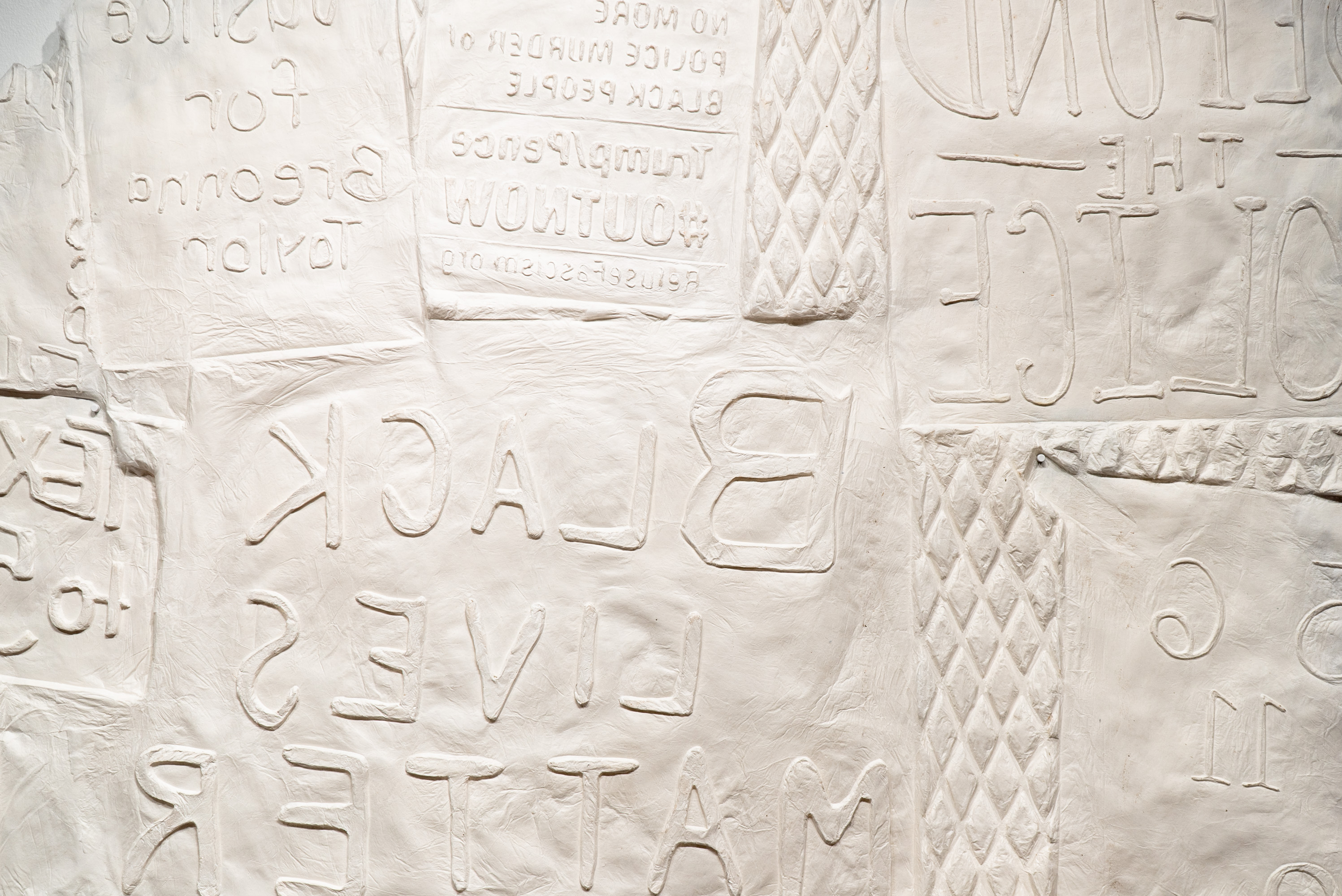

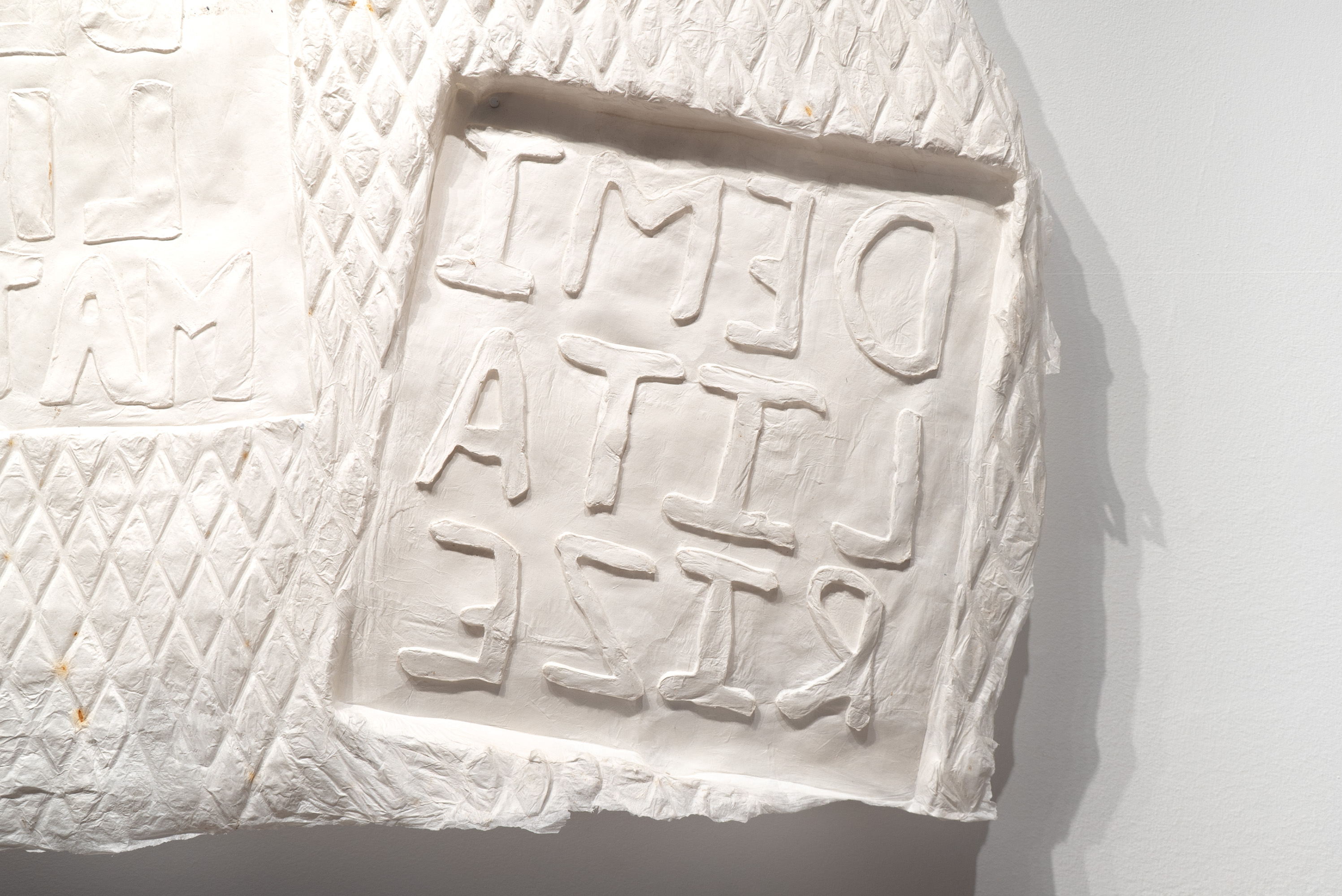

What Happens After This?

Paper squeeze is a technique similar to papier-mâché in which wet paper is pressed into a surface to make an impression and copy. Nineteenth century archaeologists like Alfred Maudslay and Lottin de Laval used paper squeeze to capture the forms of the ancient world, including Mesoamerican and Assyrian inscriptions and monuments. Sometimes the squeezes were lacquered and cast in plaster and sometimes they were displayed as-is, a negative relief of the original.

What Happens After This? uses paper squeeze in order to convey the historic and monumental nature of the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020. I recreated a life-sized section of the fencing around the White House from photos and molded it into one large sheet. By creating a contemporary artifact, I wanted to portray the protests as monumental and having lasting impact, worthy of study and admiration and wonder—like the monuments that Maudslay and others copied in their times—but also to ask, what will happen after this? Will this moment lead to lasting change?

What Happens After This?

2020

Paper squeeze

72 x 82 in.

Scenic (Re)production

Scenic (Re)production consists of stations installed at scenic vantage points along a stream in South Windham, VT. At each station, participants are invited to imagine and recreate the mechanics of the mills that shaped the economic and natural history of the area. Written prompts are given, but no other props or imagery are provided.

By reenacting the dynamics of power production in the landscape and substituting their bodies for the mill machinery, participants become part of the scenery, and onlookers are invited to photograph the landscape during these reenactments.

Scenic (Re)production

2017

3 stations with cue cards; installed in South Windham, VT

Dimensions variable

project documentation

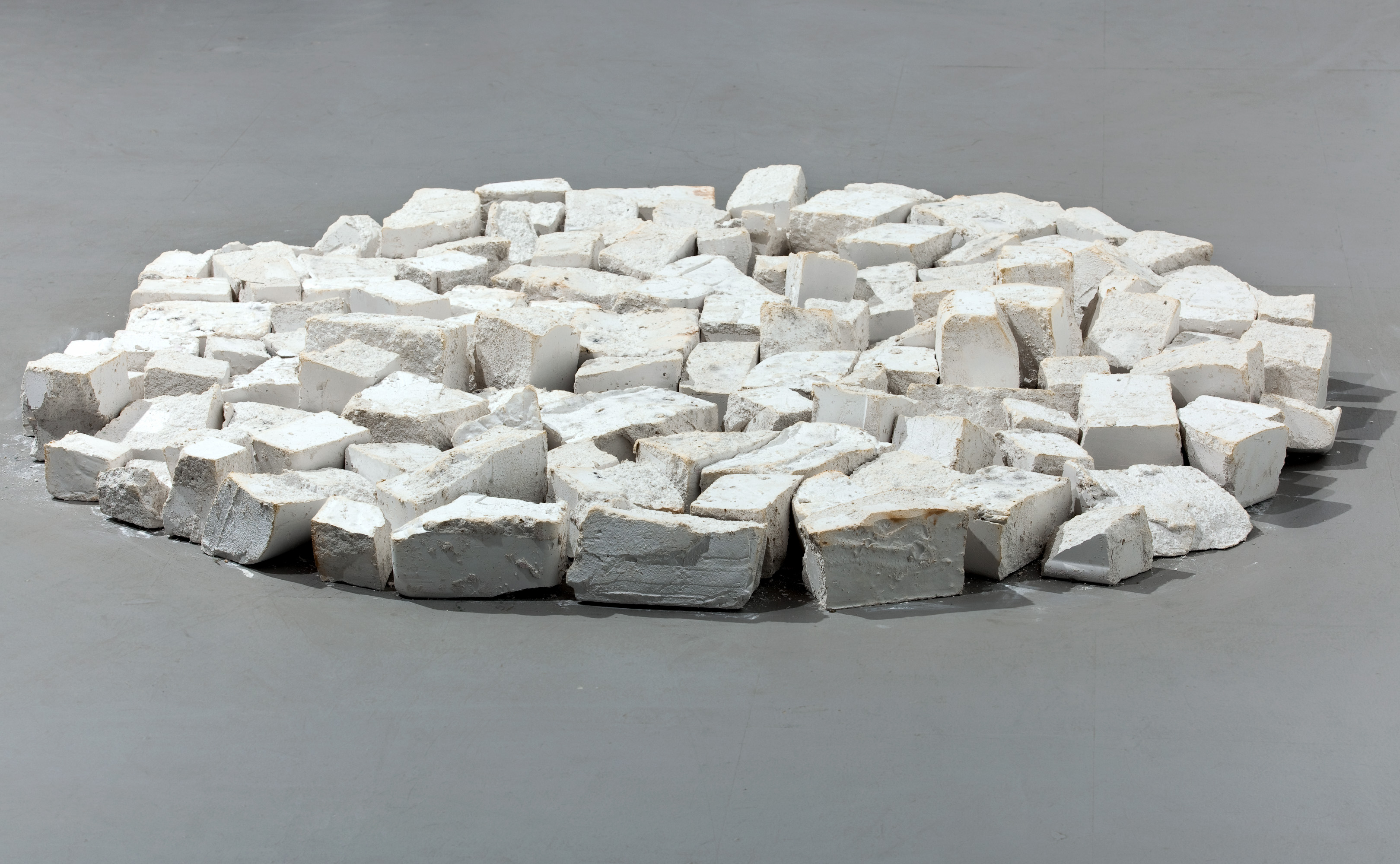

Recycling Richard Long: Gallery Walls Circle

In this work, I tried to engage with the idea of recycling as broadly and holistically as possible, with regard not only to the materials used, but also to the process of making, as well as the conceptual and aesthetic basis of the work.

I was inspired by Richard Long, who brought natural and native materials from his walks into the gallery space. Like many land artists, his work complicated and broadened ideas about the site-gallery-artwork relationship.

Recycling Richard Long: Gallery Walls Circle was also inspired by my experiences working in various museums and galleries. As a preparator, I am quite familiar with building and tearing down temporary walls for exhibitions, and I had wanted to use discarded walls as material for a new artwork for some time. Thus, my work engages with Long’s practice as a playful homage and an experiment of sorts by recycling not only materials, but also ideas.

Recycling Richard Long: Gallery Walls Circle

2009

Gypsum, recycled from temporary gallery walls, cast into blocks and arranged into a 6 ft.-diameter circle

Photos: Michael Underwood

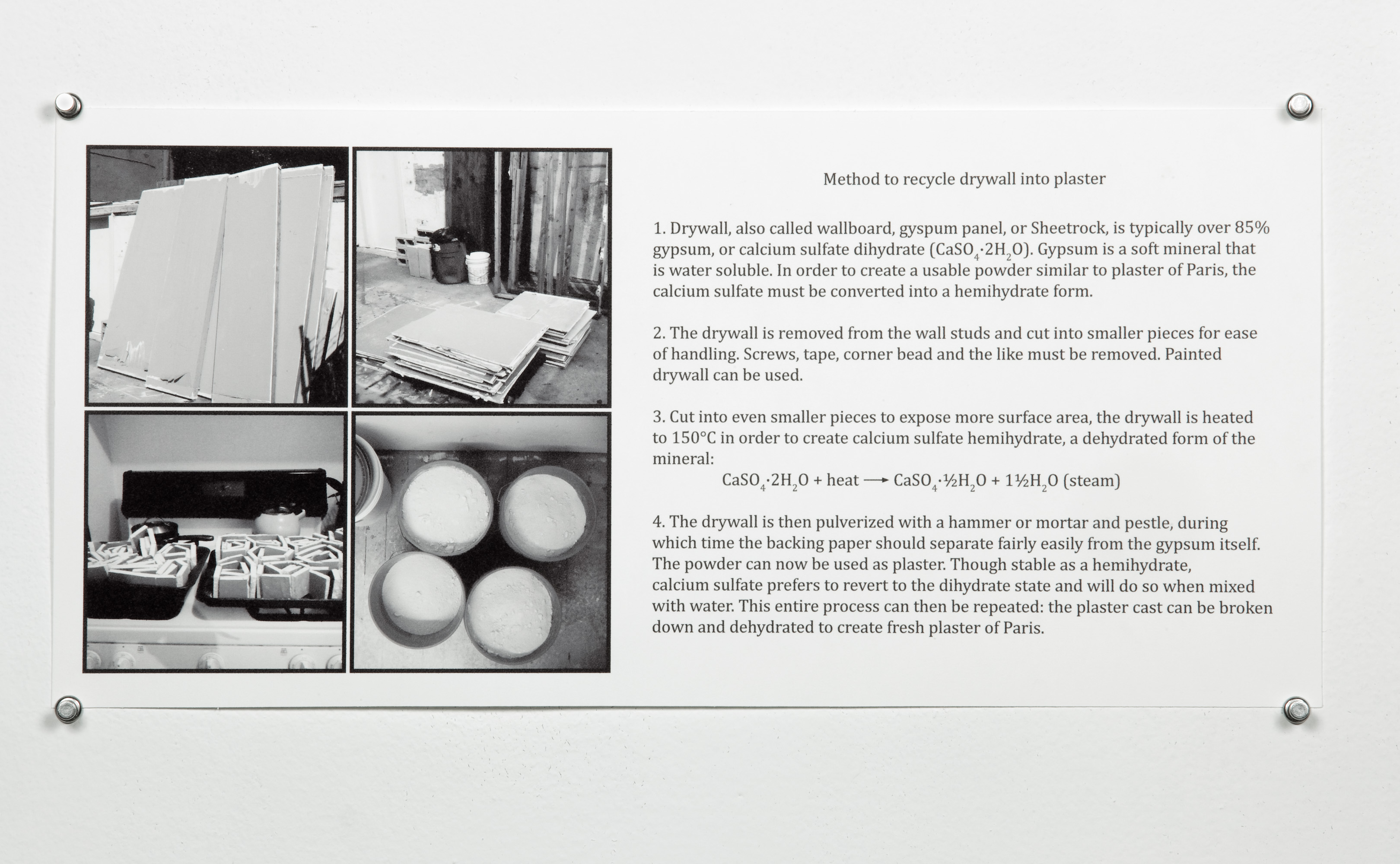

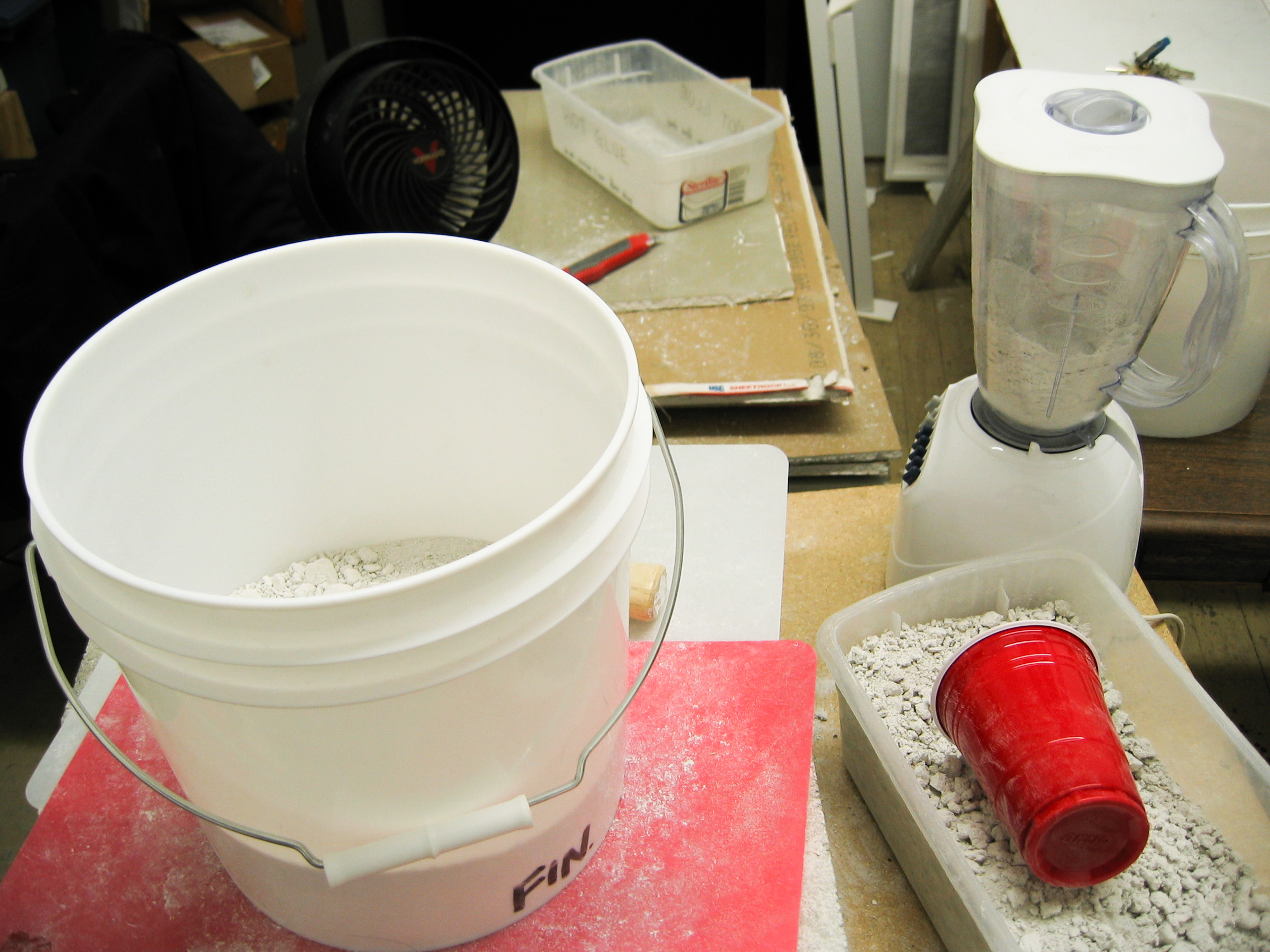

One of the stipulations that I gave myself for this project was that I would not purchase anything new. Thus the entire process of breaking down the drywall and baking and pulverizing the gypsum was quite humble and low tech. After first breaking down the drywall, I used an old blender and my oven at home to dehydrate and pulverize the gypsum before casting it into blocks using various containers that I had in my studio. The amount of material determined the scale of the work, and the final forms were determined by the process rather than a priori aesthetics.

RECYCLING PROCESS

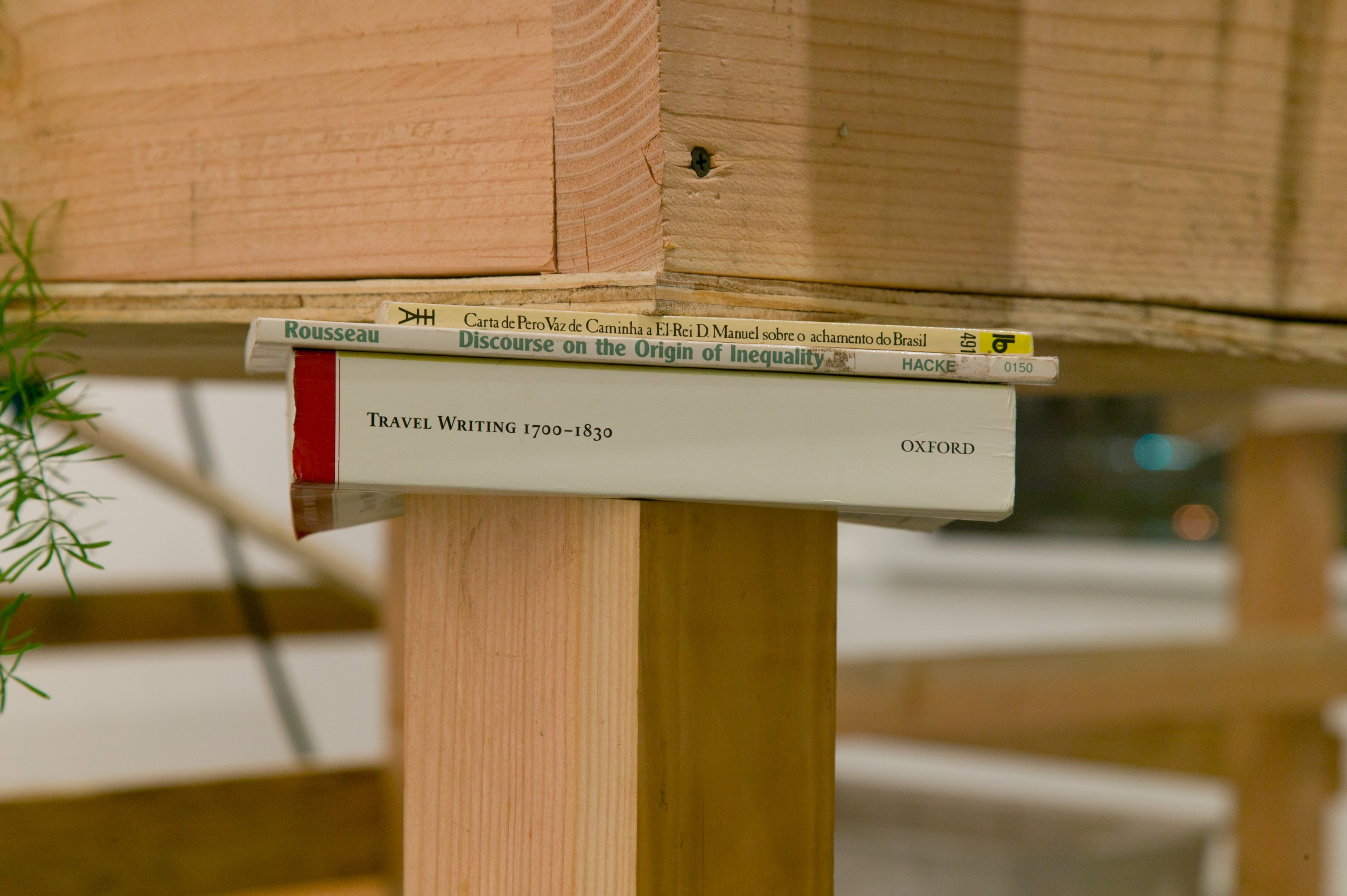

Amazon River Transplant

Growing out of the desert with reckless momentum, Las Vegas has been called a city of the future. But Vegas, like many American cities, is in desperate need of water. In contrast, the Amazon River basin has been compared to a time machine, a place lingering in an era before civilization. And no landscape on Earth is more permeated by water.

This body of work is based around a "modest proposal" to supply Las Vegas with water from the Amazon River. Part of this central conceit imagines natural resources not as commodities for human exploitation, but as being inextricably bound to both their land and their history. Thus, an unexpected, hybrid reality is created when water and local history from the Amazon is blended with the landscape and history of Las Vegas and the American Southwest. The works comprising Amazon River Transplant explore humankind's dipole fantasies of mastery over the land and reverence for an unspoiled paradise.

Amazon River Transplant

2008

Water, pumps, tubing, wood, rainforest flora, desert flora, books, informational binders

Dimensions variable

installation after 3 weeks

Post-Transplant Anomalies

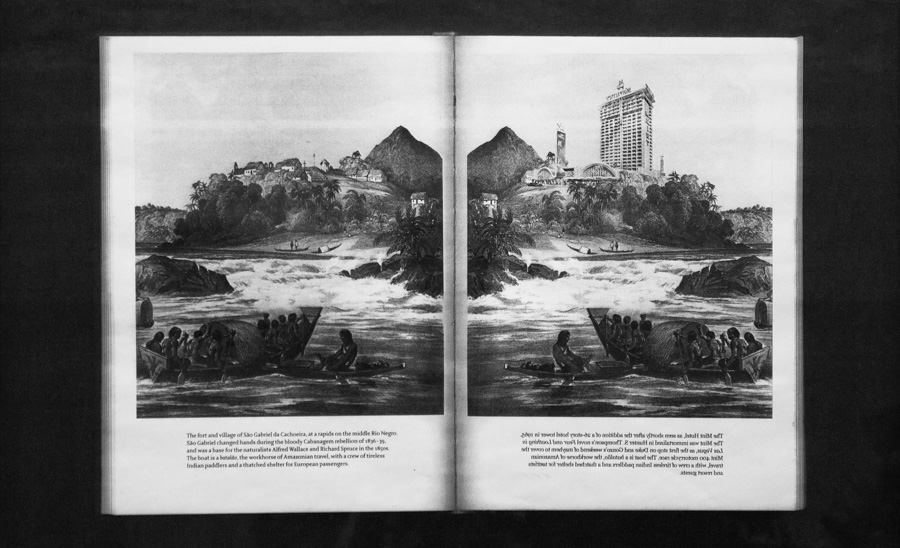

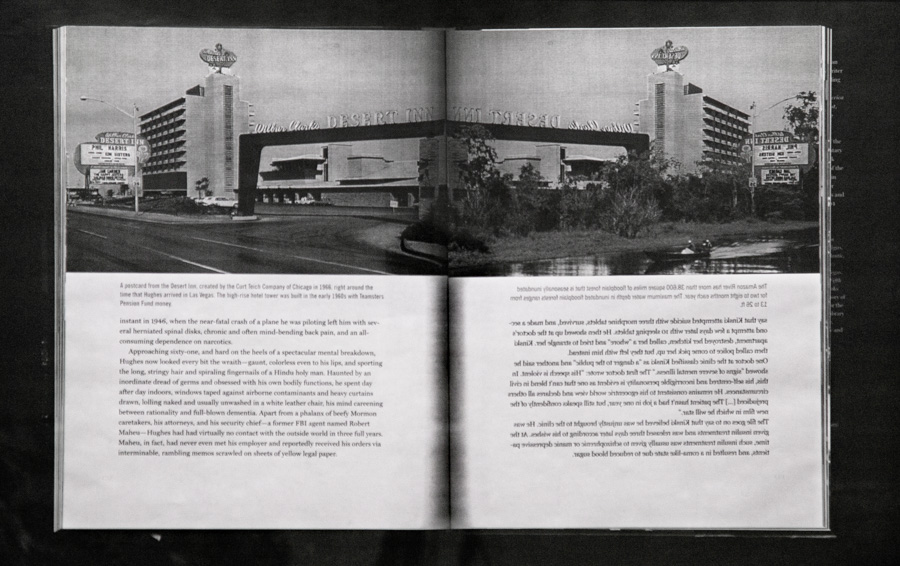

These anomalies record hybridized and overlapping realities resulting from the Amazon River Transplant. The book photocopies reveal historical narratives that have mixed and peeled away like wet ink on paper, recording an alternate (prime) history in which the Mint Hotel overlooks the village of São Gabriel, and the Desert Inn is located on the banks of the Amazon.

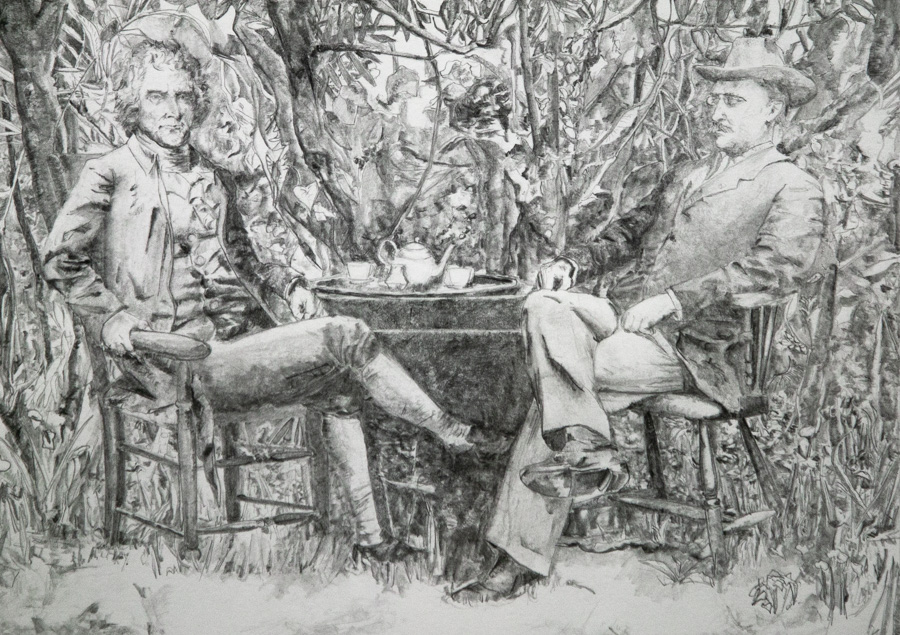

Drawings depict other events rewritten by the movement of natural resources. A meeting between Thomas Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt and the discovery of the Vegas Strip by Amerigo Vespucci represent other unlikely and unexpected convergences.

1. Pages 92 and 92′ of Tree of Rivers: The Story of the Amazon by John Hemming

2008

Photocopy

31 1/4 x 23 1/2 in.

2. Pages 192 and 192′ of Las Vegas: An Unconventional History by Michelle Ferrari and Steven Ives

2008

Photocopy

34 1/4 x 23 3/4 in.

3. Messrs. Jefferson and Roosevelt Take Afternoon Tea

2008

Graphite on paper

4. Amerigo Vespucci Discovers the Strip

2008

Graphite on paper